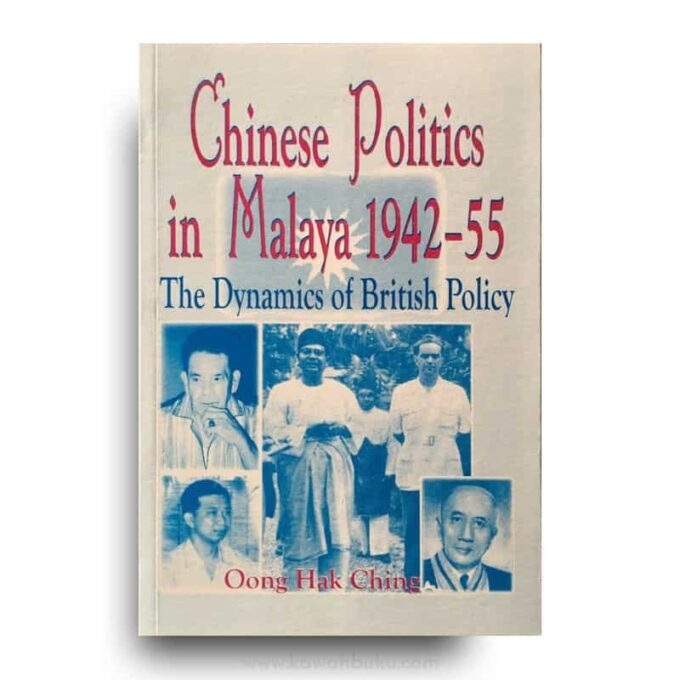

Chinese Politics in Malaya 1942-55: The Dynamics of British Policy is an attempt to assess the dynamics of British policy towards Chinese politics in Malaya. It focuses on the period from 1942-55, which witnessed the Japanese occupation of Malaya, the re-establishment of British colonial rule, and the moves towards self-government. British policy towards the Chinese community changed dramatically at the outbreak of the Second World War with the introduction of the document entitled, “Malaya, Long Term Policy Directives — Chinese Policy” and the Malayan Union proposals which replaced the British so-called pro-Malay policy of the pre-war period.

However, this new policy was suddenly changed in 1948 with the introduction of the Federal policy which practically revived the pre-war policy towards the Chinese community. At the end of 1948, the British started to rethink their position and developed a “Malayanization of the Chinese” policy. This was re-emphasized in 1952 with the development of the theme of building a united Malayan nation. 1955 was the critical year in the evolution of British policy, since this was the year that they decided to end their “rule” in Malaya.

Many books have been written which are indirectly related to British policy and Chinese politics in Malaya. In 1967, James de V. Allen wrote his pioneering monograph, The Malayan Union. It is a study of the rise and fall of the Malayan Union. The author sets himself to answer two principal questions: “Why was it attempted and why did it fail so quickly?”

Even though the monograph presented the lengthiest and most sophisticated analysis of the Malayan Union, it suffered from a deficiency of data (Mohamed Noordin Sopiee, I974). Allen’s work was mainly based on interviews and published materials including journals and books. He Was not able to examine the relevant official records such as CO273/66, CO825/42, CO865/14, CO717/152, FO371/41625 and BMA/ADM/239, which were then not yet opened for public scrutiny. Therefore, it was not possible for the author to present an entirely satisfactory explanation as to what led the Colonial Office to introduce and then to drop the Union policy. Some of his arguments are not convincing as he was not able to support them with sufficient data. For instance, he points out that one of the reasons which induced the Colonial Office to introduce the Malayan Union policy was the “anti-Malay atmosphere” prevailing at the time, along with the growth of a more genuine admiration for the Chinese, who bore the brunt of the occupying Japanese (James De V. Allen, 1967). He added that Whitehall felt that the predominantly Chinese Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) and its civilian supporters deserved some recognition and some share of the political cake after the re-establishment of colonial rule in Malaya. However, Allen fails to provide any data or specific sources to support this hypothesis.

Allen’s arguments were disputed by Mohamed Noordin Sopiee, who published From Malayan Union to Singapore Separation in 1974. According to Mohamed Noordin, there is little in the Colonial Office records “to indicate that there was a significant desire to punish the Malays or that strong anti-Malay feelings significantly affected political decision-making”. Mohamed Noordin was of the opinion that the indirect role of the United States played an important part in the formulation of the Malayan Union policy. He added that the British commitment to the ideal of decolonization also contributed to the formulation of the Union policy.

Unlike Allen, Mohamed Noordin was able to rely on a wider variety of sources—including some confidential files, particularly Cabinet papers—in the Public Record Office in London, and others in the National Archives in Kuala Lumpur. However, the work also faced a deficiency of data, as some of the relevant confidential files on this subject were opened one year after the book was published. Thus, according to Albert Lau (1911), Noordin failed “to offer a satisfactory account of official decisions at the departmental level from which the Malayan Union originated”.

Mohamed Noordin’s work, which is an overall study of political unification in the Malaysian region, gives some coverage of Chinese political activities such as the Penang Secession Movement of 1948-49. but fails to assess the impact of the Penang Secession Movement on the constitutional development of Malaya. Judging from the available information, this event in fact induced the British government to bring Singapore closer to Malaya, which in the long term contributed to the formation of Malaysia. Mohamed Noordin’s coverage of British policy towards Chinese politics in the period 1949 to 1955 does not fulfill all our expectations, particularly since more and more confidential files are available.

Another major study on the same ground is British Policy and Malay Politics during the Malayan Union Experiment 1942-48 by J.A. Stockwell (1979). As the title suggests, it focuses on the development of Malay politics, and has limited coverage of Chinese politics. In Chapter 2, the author traces and discusses the emergence of a new British policy from 1942 to 1945. According to Albert Lau (1991), Stockwell was “able to document, with greater precision, the key stages in the evolution of the Union scheme as well as presenting the first documented study of the MacMichael mission”. Like Mohamed Noordin, Stockwell (1979) found little evidence which indicated that Chinese politics had played a key role in inducing the Colonial Office to introduce the Union policy. However, he does mention that the Malayan Planning Unit appointed Victor Purcell to deal with Chinese matters. Indirectly he opened new ground for further research.

Stockwell’s work, which was published in 1979, “was understandably more extensively researched”—than either those of James Allen or those of Mohamed Noordin Sopiee. The book is heavily footnoted and makes use of almost every source available, including CO825, CO273, CO717, CO865, Cab 65/41, 49 and 53, Cab 66/60 and 65, Cab 96/5, Cab 98/41, the Malayan Security Service Files, Political Intelligence Journals, British Military Administration Files and some private papers. As his focus of research was on Malay politics, Stockwell did not investigate the work of Victor Purcell and the inter-departmental committee which was formed in December I943, to formulate a key directive on Chinese policy. As a consequence, A.J. Stockwell did not pursue James Allen’s speculations on this subject.

Nine years after the publication of Stockwell’s book, more writers began to undertake research in this field, on the basis of tackling a wider scope and more diverse literature. In 1988, Heng Pek Koon published Chinese Politics in Malaysia, followed by Richard Stubbs’ Hearts and Minds in Guerrilla Warfare: The Malayan Emergency 1948-60. In 1989 C.F. Yong and R.B. McKenna (1987) published The Kuomintang Movement in British Malaya 1912-49 and then Albert Lau’s The Malayan Union Controversy, 1942-48, published in 1991.

Heng Pek Koon’s work is the first book-length study of the Malayan (later Malaysian) Chinese Association (MCA) in the period 1945-55, which according to the author “witnessed the emergence of the Chinese as an integral component within the political community of Malaya”. Heng’s study reveals that the MCA brokered the growth of a Malayan-centered conservative Chinese political culture and, “in its finest hours… played an innovative and pivotal role in the independence movement, galvanizing and articulating the aspirations of the Chinese community, as well as effectively representing Chinese concerns vis-a-vis the British Administration and Malay powers that be.”

The real strength, which is also the real weakness of the author, are her sources. On the one hand, she was very lucky to be allowed to investigate MCA records from 1949-86 at the MCA headquarters in Kuala Lumpur and was also able to interview some prominent leaders of the party. On the other hand, she was unable to investigate a variety of other sources, including certain files in the Public Record Office and the Malaysian National Archives, and private papers such as the Gerald Templer, H.B. Ball (the Legal Advisor of the MCA) and H.S. Lee Papers.

As a result, the author emphasizes and discusses at great length the role of MCA in the process of the “indigenization” of Chinese politics and gives only small coverage to the role of the colonial government, which in actual fact, forced the Chinese to turn inward or to “Malayanize”, in order to be able to enjoy citizenship and other political rights in Malaya. There are also some gaps in her arguments relating to the origins of the MCA and the UMNO-MCA Alliance. Heng Pek Koon was not aware that Tan Cheng Lock had already made a proposal to form the MCA in December I948, as she had no access to the Malcolm MacDonald Papers. Her explanations of the origins of the UMNO-MCA Alliance were based mainly on logic, speculation and assumption (Heng Pek Koon 1988: 150-163). She also did not interview H.B. Ball, former Legal Advisor of the MCA, who could have provided some vital information regarding the origins of the Alliance. Some of her statements such as: “Rejecting Tan Cheng Lock’s decision to support the IMP in the election, the Selangor MCA leadership searched for an alternative strategy which would enable the MCA to field its candidate on a communal ticket but within an inter-ethnic framework”, are not supported by any specific source. Likewise, the author is unable to explain certain events, such as “why Tan Cheng Lock continued to support the IMP after he made his commitment to UMNO” which indicates a deficiency in documentation. Therefore, further research needed to be done or more documentation was necessary to clarify the origins of the UMNO-MCA Alliance and the attitude of Tan Cheng Lock towards the IMP and UMNO.

Richard Stuhhs’ book aimed “to place the ‘shooting war’ between the Malayan Government and the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) within the broader context of social, political and economic aspects of life in Malaya”. It made a survey of the full scope of the Government’s “hearts and minds” strategy and the impact of both Government and MCP strategies on administration, security, and political, economic and social policies (Richard Stubbs I975). His findings and analysis confirm the contribution made by his predecessors such as Anthony Short (1975) in The Communist Insurrection in Malaya, 1948-60, and complement Cheah Boon Kheng’s (1983), Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation, 1941-46. Cheah Boon Kheng, Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation, 1941-46.

To cover such a “wide-ranging review of the events of the Emergency”, Richard Stubbs (1989) mainly used a wide variety of confidential tiles in the Public Record Office and the Malaysian National Archives, mainly C0537, CO717 and CO1022 files. He missed some important tiles in the series CO273, CO865, WO203, CO1030 and also the older file FO371/116941, which could have provided some additional data on this subject. The author also failed to consult certain BMA files in the Malaysian National Archives and some private papers such as the Malcolm MacDonald and General Gerald Templer Papers (Richard Stubbs 1989).

Even though Richard Stubbs’ book offers a comprehensive explanation of various aspects of the Emergency, it also has some shortcomings. Chapter VIII, “The Final Year”, was somewhat of a disappointment as there was hardly any new information about the Baling talks of 1955. 1955 was in fact a crucial year in the development of British policy and the process of the decolonization of Malaya. He missed a chance to investigate certain files, particularly FO371/116941 and CO1030/31, which could have provided useful information, thus adding to our understanding of the British response to the communists’ peace offensiveness.

Richard Stubbs (1989:209) also gives little coverage of some of the Government’s efforts to win the “hearts and minds” of the people such as the development of a Malayan-centered Chinese political party and the Community Liaison Committee or the movement for inter-communal co-operation. Like Heng Pek Koon. he was unable to provide enough data to clarify the origins of the UMNO-MCA Alliance. He suggests that UMNO and the MCA joined forces to counter the electoral threat of Onn’s IMP, and because of personal animosity (e.g. H.S. Lee) towards Onn. But he is unable to provide any evidence to support this statement.

C.F. Yong and R.B. McKenna’s work focuses on a different angle of Chinese politics and in a different period. It is concerned with the Chinese-based political movement—the Kuomintang—in the period 1912 to 1949. According to the authors it is a study set “against the background of British Colonial rule, the changing political circumstances and fortunes in China and the rising and waning of Malayan nationalism from 1894”, (C.F. Yong & R.B. McKenna 1987). Six of the eight chapters focus on the leadership, organization and ideology of the Kuomintang in the pre-World War II period.

Generally, this book is well researched and well written and is heavily noted. The authors made use of a wider variety of sources such as official records in the CO, WO and FO series in the Public Record Office and also materials in the National Library of Singapore, private papers and other unpublished and published material both in English and Chinese. However, the authors missed a chance to investigate certain files, which are relevant to the subject, such as FO371/41625 and CAB101 in the Public Record Office, and the BMA files in the Malaysian National Archives. As a consequence, the authors did not attempt to study the evolution of British policy towards the Kuomintang during the period 1942 to 1945. The authors seemed not to have been aware of the existence of the document entitled “Malaya, Long Term Policy Directives — Chinese Policy” which was formulated by the British as a result of British (through Force 136) co-operation with the Kuomintang and the MCP during the war. Therefore, these matters remain to be redressed.

The arrival of Albert Lau’s book is a most welcome addition to the study of British policy and Chinese politics. The author presented a more comprehensive study of British constitutional policy towards both Malaya and Singapore in the period 1942 to 1948. He emphasized two fundamental aspects of British policy: the “Union” and “citizenship” issues (Albert Lau, 1991). This book definitely provides us with a more comprehensive analysis and is enlightening on the Malayan Union and the development of British policy until 1948.

The author had a great advantage compared with his predecessors in this field, since almost all the relevant confidential files had been opened in the Public Record Office and the Malaysian National Archives. Albert Lau was also able to investigate almost all MBA files and certain private papers such as the Nik Mohammed Kamil Papers, which are no longer available for public scrutiny because of the implementation of the Malaysian Official Secrets Act at the end of the 1980s.

Albert Lau (1991:74-75) made some fascinating discoveries relating to British policy towards the Chinese community during the Japanese occupation of Malaya. He also discusses the probable influence of political, moral and military factors on the Colonial Office’s thinking about its post-war Chinese policy. He made use of CAB101 files as his main source to support and justify his hypothesis and interpretation. However, without further research in this area, scholars may not be entirely convinced by his conclusions as the author has failed to indicate whether the Colonial Officers had any knowledge of the work of British Force 136 and its relationship with the MCP in Malaya before they formulated their policy towards the Chinese community.

Documents of particular significance for the subject of British policy towards Chinese politics have not been given sufficient emphasis, such as the private papers of Malcolm MacDonald, General Templer, H.S. Lee and H.B. Ball. There is also some old material which has been uninvestigated, such as FO371/416625, and there are new files to be investigated such as CO1030 and FO371/116941. Because of these documents, new information has been obtained, and a different perspective on British policy towards the Chinese has been gained, particularly the fact that previous books have under-emphasized the influence on British policy of the development of “a Chinese policy” in Malaya.

This book seeks to assess the dynamics of British policy towards the Chinese community between 1942 and 1955. A key factor in British policy towards the Chinese community was their belief that this community had the potential to become a “Fifth Column”, to serve their motherland, China, or another foreign power, notably Communist Russia. Thus, the Chinese created a so-called “Chinese problem” for the British in Malaya, including Singapore. The strength of this community lay not only in its size but also in its economic power vis-a-vis the Malays or bumiputra. The problem for the Colonial or local authorities was not to deal with and render this potential “Fifth Column” innocuous.

British policy towards the Chinese community changed dramatically between 1942 and 1955. The change took place in four phases: first, the pre-war period with the so-called “pro-Mulay policy”; second, the 1942-47 period with the new liberal Chinese policy and the Malayan Union scheme; third, the period of early Federal policy which reflected almost a revival of the pre-war policy; and the fourth phase witnessed the emergence of the “Malayanization of the Chinese” policy which aimed at building a united Malayan nation during which Britain also finally committed itself to early decolonization.

Chinese Politics in Malaya 1942-55: The Dynamics of British Policy is also intended to complement the earlier works covering the same ground and to fill the documentary gaps in this period, thereby gaining a new and fresh perspective on the complex relationships between British policy and Chinese politics in Malaya.

It is the writer’s contention that the relations between British policy and Chinese politics were shaped by the actions and responses of both parties. Between 1942 and 1946 the initiative towards a more liberal attitude towards Chinese politics was largely taken by the British without any prompting or much pressure from the Chinese. The abandonment of the Chinese policy based on the long term policy directives and the Malayan Union proposals and the implementation of the federal policy, while largely a response to strong Malay opposition, was made easier by a lack of reaction from the majority of the Chinese and the increased radicalism of the MCP. The British could still initiate a policy which affected the Chinese without giving weight to Chinese opinion. However, the introduction of the Malayanization of the Chinese policy was undoubtedly a British response to the political activities of the Chinese which went beyond an act of accommodation. It was a policy adopted to safeguard the security of the British position in Malaya and to enable the transfer of sovereignty to take place peacefully.