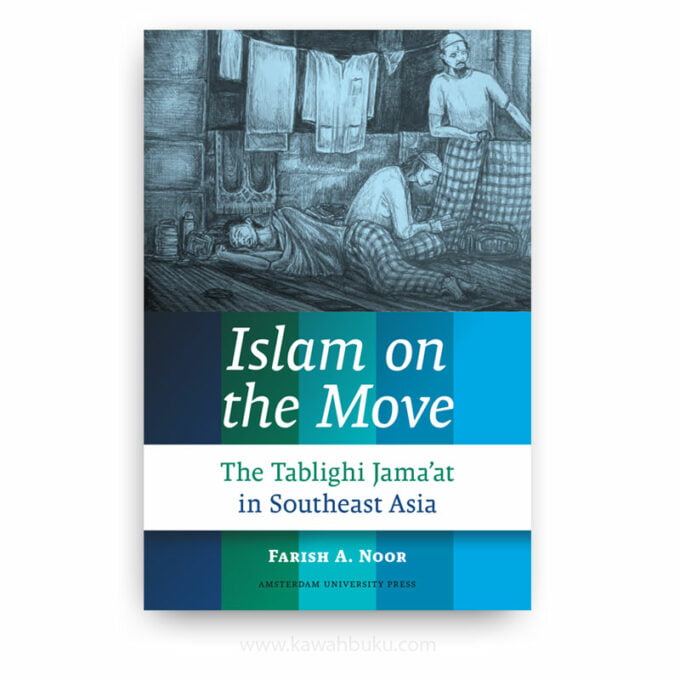

Islam on the Move: The Tablighi Jama’at in Southeast Asia set out to offer something more than simply an account of the arrival, spread, and development of the Tablighi Jama’at—arguably the biggest lay Muslim missionary movement in the world—in and across Southeast Asia. It seeks to examine the Tablighi Jama’at closely, and in the process of doing so raises a host of other questions that pertain to any study of Islam and Muslim society in general. The approach the author has taken is one that combines the study of the history of a religiously influenced mass movement with a more analytical and philosophical approach to fundamental questions of identity, subject-positioning, and representation.

For what the author seeks to do in this book is not merely to account for the Tablighi’s phenomenal success in the region but also to answer questions that are on the one hand far more basic and on the other hand more crucial to our understanding of normative Muslim religious praxis itself: what is the Tablighi Jama’at? How can we speak of there being such a thing as a Tablighi identity and subjectivity? How is the world of this Tablighi subject constructed and what are the ways and means through which such an identity can be perpetuated and reproduced over time and space? Such questions are, admittedly, more philosophical, but they are nonetheless crucial questions that need to be asked, for these are the questions that allow us to make knowledge-claims of a social phenomenon that should not be reduced to a handful of essentialist presuppositions or superficial generalizations.

Such an approach is also necessary as a result of the developments we have seen in the field of Islamic studies over the past decade, where rigor-ous interrogation of social-religious phenomena has at times been sacrificed for the sake of political expediency and the need to provide quick answers to a Muslim/Islamic question that has been reduced to the level of pathology. The framing of Islam and Muslims as a question that needs to be answered or solved is perhaps the root of the problem itself, for it could be argued that no serious study of any society, political party, mass movement, or belief system can be achieved successfully if it has been tainted by prejudice or anxiety.

The Tablighi Jama’at—perhaps because of its global outreach and visibility—has suffered from this. Some of the studies and reports on the subject, particularly by some sections of the media and the security community, have been guilty of exaggeration and hyperbole. Even worse—from an academic perspective—has been the tendency among some reporters and scholars to assume the presence of such a thing as a unified and homogenous Tablighi, held together by a closely-knit network of uniform subjectivities that see the world through a singular lens and are guided by a singular purpose. Nuance and variability have been lost in the process of this reductivist analysis, and we are all the poorer for it.

Having said that, one of the aims of Islam on the Move: The Tablighi Jama’at in Southeast Asia is to raise the question of what the Tablighi Jama’at is. But the framing of the question will be such as to preclude the possibility of easy or convenient answers, not least for the reason that the Tablighi Jama’at is a complex phenomenon that deserves a complex accounting of itself.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet