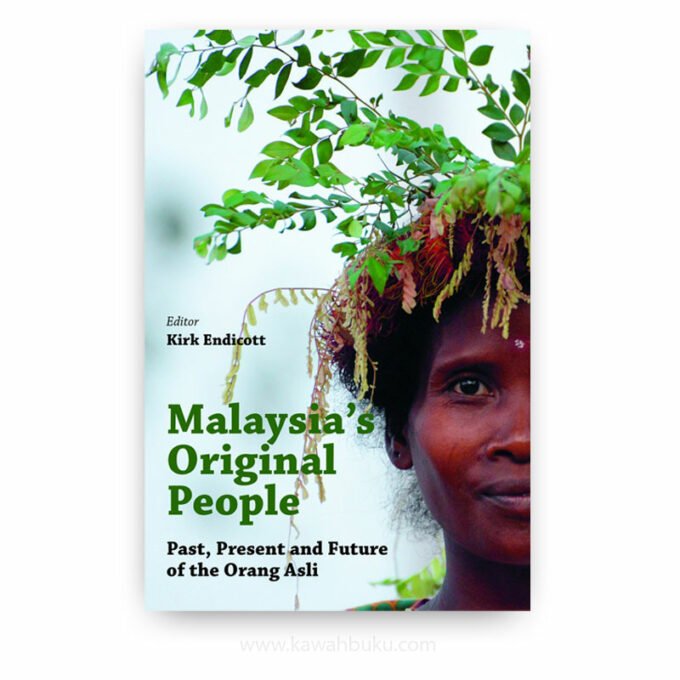

Malaysia’s Original People: Past, Present and Future of the Orang Asli is a collection of twenty-one essays that provide a comprehensive survey of current understandings of Malaysia’s Orang Asli communities, covering their origins and history, cultural similarities and differences, and the ways they are responding to the challenges posed by a rapidly changing world. The authors, a distinguished group of Malaysian (including Orang Asli) and international scholars with expertise in anthropology, archaeology, biology, education, therapy, geography, and law, also show the importance of Orang Asli studies for the anthropological understanding of small-scale indigenous societies in general.

The Malay-language term used for indigenous minority peoples of Peninsular Malaysia, Orang Asli, covers at least 19 culturally and linguistically distinct subgroups. Until about 1960 most Orang Asli lived in small camps and villages in the coastal and interior forests, or in isolated rural areas, and made their living by various combinations of hunting, gathering, fishing, agriculture, and trading forest products. By the end of the century, logging, economic development projects such as oil palm plantations, and resettlement programs have displaced many Orang Asli communities and disrupted long-established social and cultural practices.

An introduction by Endicott that begins with invaluable ethnographic information about what the term “Orang Asli” entails, their demography, areas of habitation, and social organization launches the book and covers an enormous range of issues on what it means to be Orang Asli in a rapidly changing world. The volume is divided into seven parts. Each is devoted to a different theme, yet together they weave together remarkable insights that advance our understanding of the historical continuities and disjunctions in Orang Asli landscape, history, and identity.

The themes of the book display comprehensively the broad interests of Orang Asli specialists. We are shown stunning insights into fieldwork methods, ways whereby the Orang Asli perceive webs of interconnectivity, their enormous ability to adapt to new situations, and how western communities have much to learn from Orang Asli cultures. All these are at once a meditation on questions central to the way we think about human history, human ecology, and human creativity, as well as a path to multiple discourses into wider analytical, methodological, and epistemological questions.

While the book deals with a range of Orang Asli communities and while contributors approach the topic from different vantage points, Endicott’s organization helps maintain greater coherence than is the case in many collections, and there is at least some indication of communication between chapters. Overall, however, readers are presented with two lines of thinking: on the one hand, a number of chapters paint a bleak picture of the Orang Asli as they strive to adjust to the changes that have penetrated so deeply into their lives. The readers are shown, for instance, that negotiation of outside influences makes an Orang Asli village a ‘contested site’, and that in numerous cases the loss of forest and hunting areas, the decline in indigenous knowledge, and the stresses induced by modernity raise real doubts about the survival of smaller groups.

On the other hand, other chapters argue that the adaptive strategies will enable at least some Orang Asli groups to retain a sense of their cultural identity and counter the many challenges they face. Yet whatever the viewpoint adopted, one must accept that this book is above all one of advocacy. Certainly, Malaysia’s Original People: Past, Present and Future of the Orang Asli is extraordinarily successful in generating empathy for the Orang Asli plight and admiration for their endurance.

Quick delivery