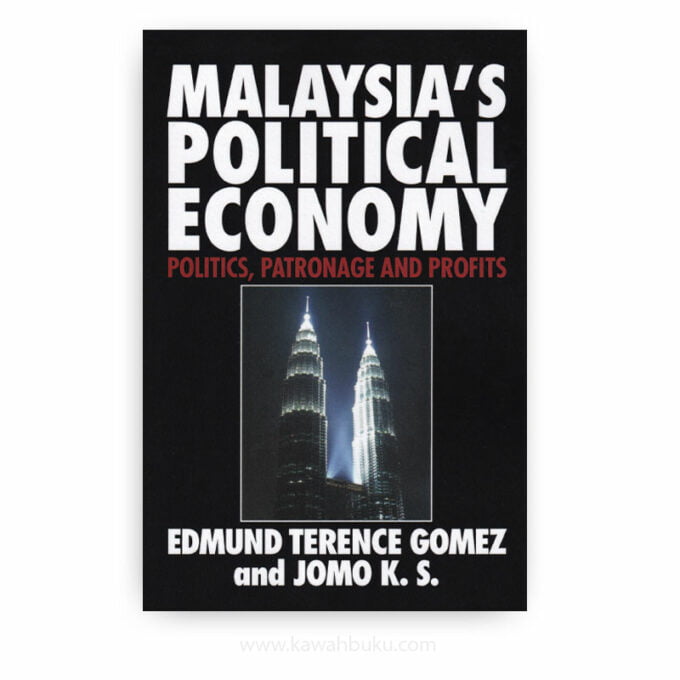

Malaysia’s Political Economy: Politics, Patronage and Profits explore how political patronage influences the accumulation and concentration of wealth by using the concepts of rent and rent-seeking as tools to study the Malaysian political economy. The book considers the impact of party politics and economic development on the relationship between politics and business in Malaysia and provides discussions of government-led change in Malaysia’s business community, including the emergence of a Malay business class. In this revised edition, the authors examine how the 1997 Asian currency, liquidity and financial crises have impacted Malaysia’s economy. Their discussion canvasses various economic policy responses, including capital control measures, as well the ensuing economic recession and political turmoil.

The authors have produced an insightful and richly documented analysis of Malaysia’s political economy during the quarter-century from the launching of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1970 through the mid-1990s. It serves as a useful introduction to the current (1998) economic crisis and the political warfare between Prime Minister Mahatir Mohamed and his former protégé and Finance Minister, Anwar Ibrahim. Their major thesis is the prominent role of political patronage and clientelism by which an increasingly authoritarian and centralized Malay political elite surrounding the Prime Minister employs the financial resources of the state to distribute control of major economic enterprises to a small circle of dependent cronies and quasi-entrepreneurs, often by methods that are shrouded in secrecy and savour of corruption.

The ostensible rationale for this ethnic redistribution of assets was to increase the Malay ownership share in the corporate sector of the economy from a negligible 2.4 per cent in 1970 to 30 per cent over a twenty-year period, thus eliminating the identification of “race” (ethnicity) with economic function. This was to be accomplished originally by massive intervention by which state enterprises would acquire and hold shares as trustees for the Malay community, then divest them (privatization) to selected Malay individuals with close links to the governing elite. The results have been impressive: by 1990 Malays owned and controlled a conservatively estimated 20 per cent of an economy that had expanded by a factor of four, without penalizing non-Malays (mainly Chinese). The non-Malay ownership share also grew at the expense of foreigners whose assets were purchased by government agencies.

Unlike many economists, these authors appear to accept the political necessity for government intervention to enhance Malay participation in the modern economy, even at some cost in economic efficiency. What they deplore, however, is that the new class of Bumiputera (Malay) capitalists are neither authentic entrepreneurs nor

industrial managers. They have not built and managed enterprises from the ground up; with few exceptions, they have developed no expertise in production, marketing, technology or management. Instead, they function as financial manipulators, engaged in deal-making, swapping shares, asset stripping, and conglomerate building, benefitting from rents of various kinds, including financial subsidies (access to capital on concessional terms), lucrative noncompetitive contracts from government agencies, and protection from foreign competition. They fail to contribute to the efficiency, productivity, diversification, or international competitiveness of the Malaysian economy.

As clients to influential politicians, they become embroiled in factional struggles within the leadership of UMNO, as their competing patrons vie for power. UMNO elites have also learned to manipulate share markets to raise funds for political campaigns, effectively reducing their former dependence on wealthy Chinese and the influence of the latters’ political vehicle, the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA). The MCA had, since Independence, assured the Chinese a junior role in the consociational Alliance-National Front governments. This has, in turn, forced wealthy Chinese to resort to coopting strategically placed Malays into their enterprises-similar to the methods employed by overseas Chinese in Thailand, Indonesia, and other Southeast Asian countries.

Yet, in response to the severe economic downturn in the late 1980s, the government has moderated its practice of Bumiputera preference and relaxed its restraints on non-Malay enterprises in order to foster modernization and international competitiveness now that the NEP’s ethnic redistribution goals have come close to realization. But while interethnic distribution of income has improved, as intended by the NEP, intraethnic distribution has deteriorated, especially among Malays. Rapid economic expansion has, nevertheless, trickled down and spread its benefits widely, creating job opportunities that greatly reduced the incidence of absolute poverty among Malays.

The themes presented in this book are not original, but they are developed and documented with abundant and convincing detail. The eleven case studies appended to three of the chapters illustrate the byzantine complexity of the deals, manipulations, and political shenanigans that characterize the operations of the new Bumiputera capitalists and their political patrons. Though written and published before the 1998 crisis, this study describes and analyzes the loose financial practices, the pervasive subsidies, and the cronyism that, along with currency speculation by foreigners, contributed to the current malaise. The political economy approach is especially useful in illuminating the close interlinking between political power and economic policy and practices.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet