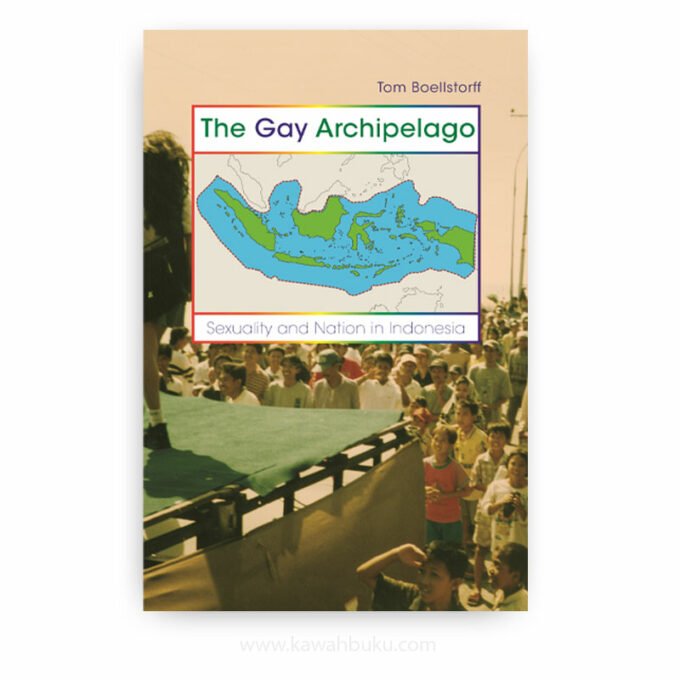

The Gay Archipelago: Sexuality and Nation in Indonesia is the first book-length exploration of the lives of gay men in Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous nation and home to more Muslims than any other country. Based on a range of field methods, it explores how Indonesian gay and lesbian identities are shaped by nationalism and globalization. Yet the case of gay and lesbian Indonesians also compels us to ask more fundamental questions about how we decide when two things are “the same” or “different.” The book thus examines the possibilities of an “archipelagic” perspective on sameness and difference.

Tom Boellstorff examines the history of homosexuality in Indonesia, and then turns to how gay and lesbian identities are lived in everyday Indonesian life, from questions of love, desire, and romance to the places where gay men and lesbian women meet. He also explores the roles of mass media, the state, and marriage in gay and lesbian identities.

The Gay Archipelago is unusual in taking the whole nation-state of Indonesia as its subject, rather than the ethnic groups usually studied by anthropologists. It is by looking at the nation in cultural terms, not just political terms, that identities like those of gay and lesbian Indonesians become visible and understandable. In doing so, this book addresses questions of sexuality, mass media, nationalism, and modernity with implications throughout Southeast Asia and beyond.

The study, born of Boellstorff’s long-time academic and activist commitment, is an attempt to transcend existing literature on sexuality and globalization that defaults into the common interpretative binarism that either the world is shrinking towards a uniform Gay Planet of Western-like similitude, or non-Western traditional same-sex practices are resisting the globalizing pressure and remain unbridgeably different and sufficiently ‘authentic’ objects of conventional anthropological analysis. Boellstorff advocates an intersectional approach to the study of sexual cultures and subjectivities, by focusing on the birth of the modern Indonesian state, thus overcoming the previous regional focus. The question is not whether globalization makes the world more the same or different, but that contemporary complex processes of change are reconfiguring the yardstick by which the grid of similitude and difference is interpreted.

In the section ‘Historicity of homosexuality in colonial Indonesia’, Boellstorff rejects a clear-cut temporal trajectory connecting present-day gay and lesbi with ‘indigenous’ traditional homosexualities. Instead of assuming that the existence of non-normative sexualities in Indonesia’s past constitutes present gay and lesbi identity in embryonic form, or that indigeneity is required for modern phenomena to be authentic and ‘really’ Indonesian, Boellstorff skilfully documents past non-conforming sexualities, such as the transgender bissu and waria. He shows that various gendered and sexual practices were widespread, but that they have little in common with contemporary gay identity. The question of producing temporal and cross-cultural convergence, while crucial to Western gay culture and ideology, is not experienced as meaningful for most gay and lesbi; rather it is the importance of = national belonging, legitimated by aspiring to be a good citizen through choosing family life.

Gay and lesbi subjectivities emerged in the context of modern postcolonial Indonesia under Soeharto’s regime since 1970. The heteronormative ideal family based on an ideology of national love and individual choice, and opposed to ‘traditional’ practices of arranged marriage, is crucial to this project. Heterosexuality and national belonging were preconditions of postcolonial modern Indonesia, were mass media’s reporting of non-conforming sexuality at home and abroad unintentionally enabled gay and lesbi subjectivities to emerge on a national scale, binding them together ‘archipelago-style’ across the island nation.

By ‘dubbing’ foreign-originating media images of sexuality and reflected through a new nationalistic lens, and at the same time choosing conventional heterosexual marriage and family life, Indonesians appropriate gay and lesbi notions in creative ways that include them in the modern nationalist project, as citizens of the Indonesian nation. Being gay or lesbi is thereby not antithetical to the current family ideal. Yet, this ‘dubbed’ citizenship disables a total synchronization of non-normative desires and practices with fully normative citizenship. A wonderful and intimate ethnography of gay and lesbi sexuality, love, desire, and family supplies fascinating detail to the analysis.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet