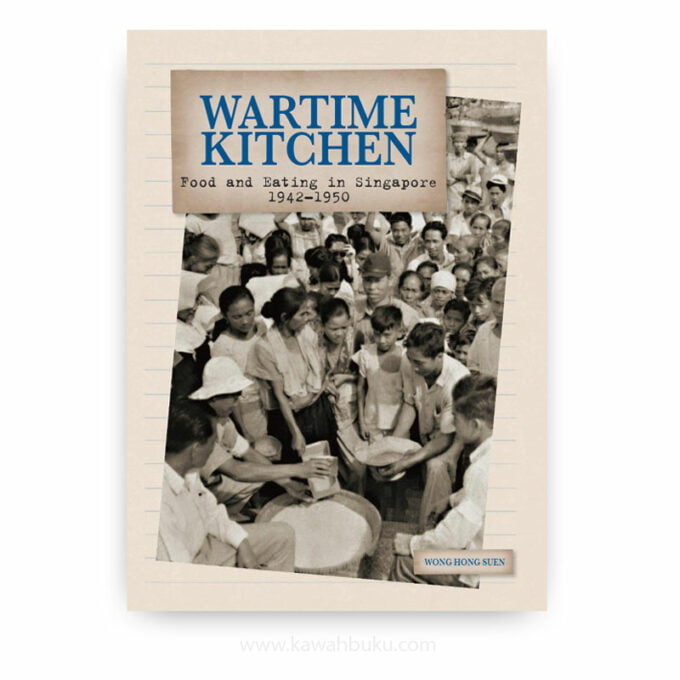

Wartime Kitchen: Food and Eating in Singapore, 1942-1950 captures the resilience and adaptability of a people faced with limited resources and shortages during the Japanese Occupation and in post-war Singapore, never before examined in detail. How people adapted to shortages, especially in terms of food, is thus the focus of Wartime Kitchen. How did people cope with the new food regime of rationed goods, bureaucracy and unpredictable supply? How did they sustain themselves by exploiting opportunities in varied and imaginative ways? The book examines the experience of people from the fall of Singapore in December 1942 up to 1950. The return of the British in September 1945 did not bring about a significant immediate improvement in food supply and required continued adaptation to food shortages.

The people of Singapore found themselves unable to obtain enough food, especially rice, in the face of the shortage of supplies and escalating prices. By the end of 1942, prices were 12-15 times their pre-war level. NI Low, who was an Assistant Supervisor of Private Schools before the Japanese Occupation and who later became the Headmaster of a Japanese school, noted that the price of a kati (about 600 g) of rice rose from $5 (Straits Dollars) in December 1941 to $5,000 (Japanese wartime currency) in June 1945. In 1946, a year after the Japanese surrendered, an interim report by the Wages and Cost Of Living Committee under the British Military Administration (BMA) revealed that prices (of all essential items) were 352% higher as compared to 1941 before the war broke out.

Existing literature on wartime Singapore and life during the Japanese Occupation have generally been studies that

span the following topics—bombing and air raids, Japanese atrocities, rationing, the black market, transport, banana notes, education, entertainment and propaganda. None have focused on food and eating, or specifically the lack of food, which for many survivors remain the defining aspect of life during the war and the few years after liberation.

Wartime Kitchen delves into the details of food and eating drawn from interviews, autobiographies and memoirs. It is a miscellany of memories that are valued for how they reveal the textures of everyday life, lend immediacy and vividness to events, and flesh out the details embedded in archived records. These memories serve to complement but also contrast official narratives (such as school textbooks) of wartime Singapore. Newspapers such as The Syonan Shimbun and The Straits Times are crucial sources of general information related to the administration’s food policies and implementation; as well as for details such as food supplies and their sources. Unless otherwise indicated, all such information is obtained from the various newspapers consulted.

This book focuses on the memories of the local population rather than that of the expatriate, which includes the officers and men of the British and Australian military forces and the European civilian internees. The latter remains a distinct and important set of memories but have been documented extensively in both personal accounts (such as Caffrey Kate’s Out in the Midday Sun [1974], T Lewis’ Changi: The Lost Years, a Malayan Diary 1941-45 [1984] and Gladys Tompkins’ Three Wasted Years: Women in Changi Prison [1977]) and secondary literature such as Van Waterford’s Prisoners of World War Two [1994].

In reconstructing the history of food and eating in wartime Singapore, Wartime Kitchen has taken into account personal recollections such as Chin Kee Onn’s Malaya Upside Down [1947], one of the earliest and most detailed first-hand accounts of life under Japanese rule; as well as comprehensive studies that have drawn from both personal memoirs and archival records, statistics and newspapers such as Paul Kratoska’s The Japanese Occupation in Malaya 1941-1945: A Social and Economic History [1998] and the richly illustrated book by Lee Geok Boi entitled The Syonan Years: Singapore under Japanese Rule 1942-45 [2005].

A great read.