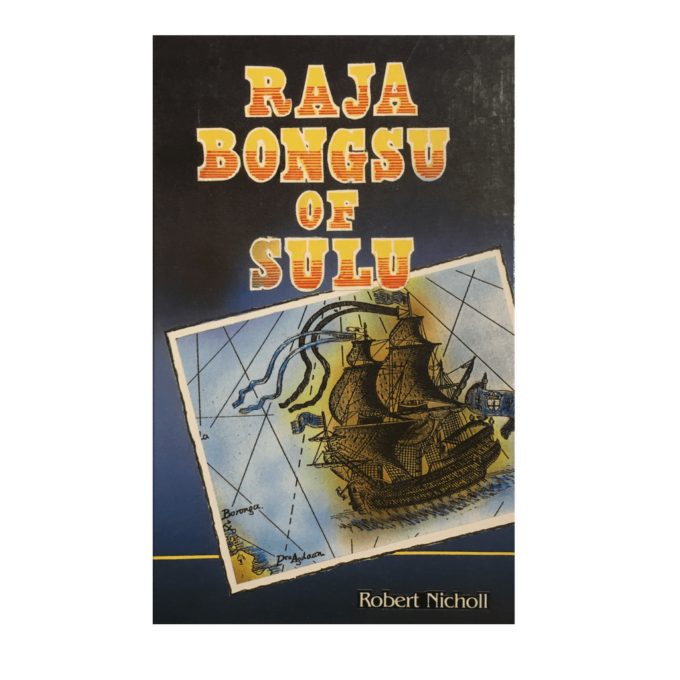

Raja Bongsu of Sulu: A Brunei Hero in His Times is an account of Raja Bongsu’s life by Robert Nicholl, a slim and scholarly volume that sets out to render a factual account of the life and career of the eponymous semi-mythological figure, a princeling of Sulu who flourished in the first half of the seventeenth century. Hampered by a patent lack of clear biographical details, Nicholl succeeds in constructing a convincing account of the legendary figure remembered for his courage in repelling the Spaniards out to gain control of the strategic Sulu Archipelago in the seventeenth century.

Armed with his formidable knowledge of mediaeval Brunei history, Nicholl also charts the early linkages shared between the royal kingdoms of Brunei and Sulu, two of the most powerful sultanates in Borneo at the dawn of European colonialism in Southeast Asia. What results is an exciting account of the first of the Moro Wars between the indigenous Muslims of South Philippines and the marauding Spaniards, set out against the backdrop of conflict between the Dutch, the Spaniards and the local Muslim kingdoms which began went on throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Conflict has remained a persistent characteristic of this particularly turbulent region and has remained so to this very day, as seen in the ongoing demands for greater autonomy by the indigenous population of South Philippines from the Philippine Government.

Of Raja Bongsu himself nothing further is recorded. He was certainly living when Combés was writing his great Historia, 1662-1664, and the two seem to have been acquainted, for the Raja showed the historian the scars of the wounds that he had received as a boy, when trying to defend Pengiran Tindig. Combes had been frequently employed by the government at Manila as an envoy to Muslim rulers, and it was probably in this capacity that he met both Raja Bongsu and Tuambaloka; they must have made a favourable impression upon him, for his references to both are sympathetic. But Combés’ text provides no clue as to what happened to the Raja after his retirement in favour of young Bakhtiar c. 1650.

Did he like Datu Aceh return to Brunei, or did he join Tuambaloka to Basilan?

Both seem improbable in view of his attachment to Jolo and its people. The fact that in his lifetime in 1663 his successor was still referred to only as Pengiran Bakhtiar, suggests that the Tau Sug datus insisted that he keep the title of Raja, even though his infirmities prevented him from ruling, if this were the case, then it is reasonable to suppose that his bones rest on Jolo. Later, after the creation of Bakhtiar as Sultan of Sulu, the Datus posthumously raised Raja to the Sultanate as Sultan Muwallit Wasit, and as such he achieved honourable mention in the Khutbahs and Kitabs.

In many ways Datu Aceh is a much more glamorous figure than the Raja Bongsu. The Datu was the greatest native warrior of his day in the whole region, at once admired and feared. The Raja was second to none in courage, but he was also a ruler, and it is as a ruler that he must be judged. The measure of a ruler’s greatness is his subjects’ affection for him, and here Raja Bongsu stands high. For twelve months after the surrender in April 1638 he was able to remain in Jolo, a fugitive hunted by the Spaniards, yet always concealed by his people.

When in June 1639 Don Pedro de Almonte had finally cornered him, the inhabitants of a small kampong fought to the last man to give him time to escape: “Many Muslims paid with their lives for this signal demonstration of their love for their King.” This simple testimony writ in blood says all: to his people Raja Bongsu was a hero.