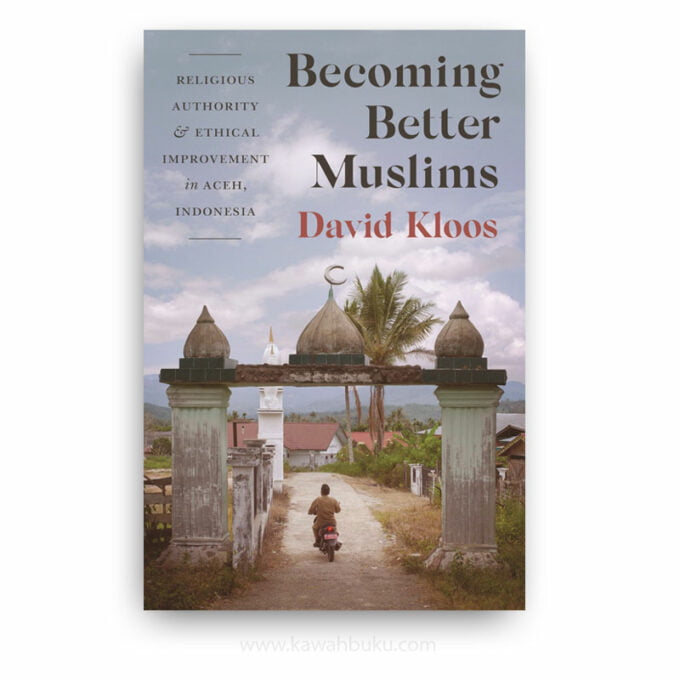

Becoming Better Muslims: Religious Authority and Ethical Improvement in Aceh, Indonesia frames the devotional transformations experienced by Aceh’s men and women, young and old, in their everyday life in the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami. In a smooth and persuasive narrative, Kloos walks the reader through an analysis of the Acehnese people’s piety from the colonial period—focusing on how the Dutch framed and ultimately shaped various understandings of this piety—to today. Becoming Better Muslims makes an important contribution to scholarship on South East Asia, the study of Islamic societies, and anthropology; it will also be of interest to scholars and students of Acehnese history, colonialism, religious studies, and political sciences. Kloos’s analysis touches on a number of compelling topics, from everyday devotion to aspirational piety; contextualization of religious authority and normativism; the nexus between religious piety and natural disasters; and the legacy of colonial knowledge production on the shaping of religious identities and policies in post-colonial states.

Following an introductory chapter that lays out the setting and approach of the book, the first two substantial chapters respectively address the impact of the colonial experience on the Acehnese people’s relationship to Islam and the inefficiency of thinking about Aceh—often dubbed ‘Mecca’s verandah’ because of its geographical location as much as the perceived piety of its inhabitants—as a site of exceptional Islamic devotion vis-à-vis the rest of the region. Kloos aims to unpack the Dutch colonial imagination of Aceh ‘as a particularly “pious” place’ and of the Acehnese as an extremely devout, and therefore rebellious people.

Kloos identifies an important dichotomy in the Dutch approach, which pitted ‘remote’ rural Muslims, who followed ‘vernacular’ or ‘mystical’ devotion and authority figures, and were ‘susceptible to ideas about “holy war”’, against ‘correct’ Islamic behaviour that rejected all those other practices in the name of a ‘modern’ take on religion. Representatives of the latter group eventually also embraced Western forms of modernity and were thus regarded even more favourably by the Dutch; this established the primacy of ‘modernist’ or ‘reformist’ Islamic associations in Aceh.

Chapter 2 then moves on to ask ‘how the state was embedded in Acehnese society … and how this process influenced local contestations about religious practice and authority’ during the revolutionary period (often referred to as a ‘social revolution’ because of the deep transformations in local structures of authority), Aceh’s incorporation in the Indonesian nation-state, and Suharto’s New Order. Addressing head-on ‘the limits of normative Islam’, Kloos points out how even during the heyday of the Aceh off-shoot of the Darul Islam movement—which had originated in West Java in the 1940s to advocate and fight for an Islamic state of Indonesia—’established religious practices condemned as heretical did not necessarily, or all of a sudden, disappear’. Throughout the 1960s, the people of Aceh Besar, in fact, continued to perform visits to graves and to seek help from healer diviners.

As Suharto’s New Order created new social and political structures, ‘traditionalist’ and ‘modernist’ factions further polarized in response to ‘the changing nature of the state’, but–at least according to the notes of Chandra Jayawardena, from which Kloos draws extensively—’the forces of state and religious authority, as powerful yet flexible domains of moral practice and disposition, simultaneously allowed for and obstructed the adjustment and adaptation of normative Islam’.

The second part of the book focuses on contemporary Aceh and the lives of Kloos’s cast of characters. The ethnographic material is reconstructed around three core themes, namely moral authority, post-disaster piety, and ethical improvement. ‘Village society and moral authority’ brings into focus the combination of socio-political and generational tensions, as Kloos explores the interrelation between the religious leadership of the dayah (Aceh’s traditional Islamic schools) and ‘secular’ politics in the village, and the conflict between the elderly and youth, as ‘young people today are prepared, much more than their elders, to accept and act upon the role of traditional ulama as agents of the state’.

Chapter 4 builds on these same ‘concepts of community, shame, respect, wealth, and punishment’ in the context of renewed piety after the shock of the tsunami. For many, this event pointed at the ephemerality of material possessions, or the need to behave in this world with one’s eyes (and heart) on the afterlife. Kloos works through these narratives with the challenge of designing ‘conceptual and interpretative frameworks that allow us to explore the dynamic relationship between religious commitment and the unruly reality of, and fragmentation of, everyday lives’, or, in other words, ‘the relationship between personal processes of ethical improvement and the social and political contexts in which these processes take shape’. Within this framework ‘the formation of a personalized religious agency’ emerges as the key element in explaining Aceh’s post-disaster religious revival.

Chapter 5 is the de facto concluding chapter, as it focuses on ‘personal behavior, morality, and formal disciplining’ in contemporary Aceh, where personal projects of ethical improvement interface with formalized sharia-inspired laws. Kloos suggests that taking responsibility for, and reducing, sinfulness represents ‘a crucial dimension of religious agency in Aceh, namely the role of self-perceived moral failure in processes of ethical formation’. This is especially significant, as the implementation of shari’a-compliant laws seems to ‘have failed to achieve their goal of “perfecting” official norms both among individual Muslims and in Acehnese society at large’. Kloos shows how—in a province where laws have been reformulated to comply with Islamic principles—individual Muslims’ trajectories of ethical and moral improvement are mostly grounded in personal reflection and action, unveiling a ‘religious agency [that] reflects a perception of religious consciousness and associated action that allows for certainty and truth as much as ambivalence, doubt, and imperfection’.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet