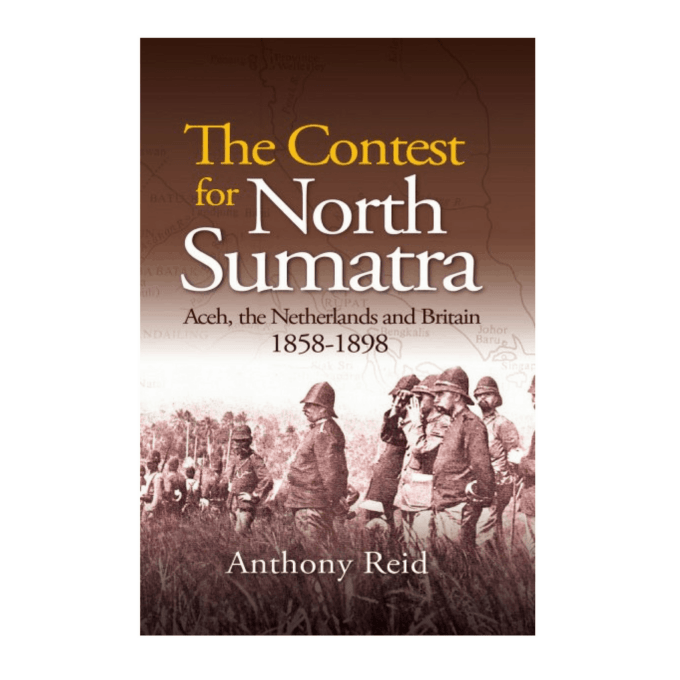

The Contest for North Sumatra: Aceh, the Netherlands and Britain, 1858-1898 describes the painful transition of North Sumatra from a number of independent states to a part of Netherlands India (present day Indonesia). It is seen not as a simple conflict of Netherlands imperialism and Indonesian parochialism, but as a three-sided contest in which the independent commercial interest of the Straits Settlements played an integral role. Aceh and Oostkust van Sumatra were the last to resist Dutch influence because they were almost exclusively the commercial preserve of Britain. It was not until the end of the century that the Netherlands overcame this difficulty and established her claim over the whole area, giving way to the demands of British commerce in the East Coast but ignoring them in the case of Aceh.

North Sumatra was a different matter. Its people were warlike, more unified, and marked with religious zeal. Its trade at this time was almost entirely with Britain’s Penang entrepot. At the same time the Treaty of London of 1824 denied both Britain and the Netherlands political control. By 1870, however, the “unmistakable liberal trend in Dutch commercial policy after 1848” and the facts of life of the age of neo-imperialism convinced the British Foreign Office that it was better to see this region along the strategic Straits of Malacca “in Dutch hands than in those of some stronger Power”. The Sumatra Treaty of 187I—”a disservice to both British and Dutch interests” and “a much greater disservice to the Acehnese”—in effect, sealed Aceh’s fate.

The author provides a good account of the painful period which follows: the (unofficial) activities of representatives of a number of foreign powers (the United States and Italy), Acehnese diplomacy (carried out by the remarkable Abd ar-Rahman and the “Council of Eight” in Penang), the unpreparedness and vacillation of the Dutch, and the cramping influence which Straits Settlements’ protests had on Dutch policy and action. Only in the 1890’s did the Dutch overcome their anxieties of British reactions by adopting a more vigorous blockade of Aceh’s north coast and an administrative policy which fitted Aceh’s dependencies into what became the centralized structure of the Netherlands Indies. It is the author’s contention that Dutch statesmen long and unduly exaggerated “the importance of avoiding hostile reactions among the Straits merchants because it suited their traditional and economic policy of non-interference”.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet