The dark side of Pramoedya Ananta Toer

By Johan Jaaffar

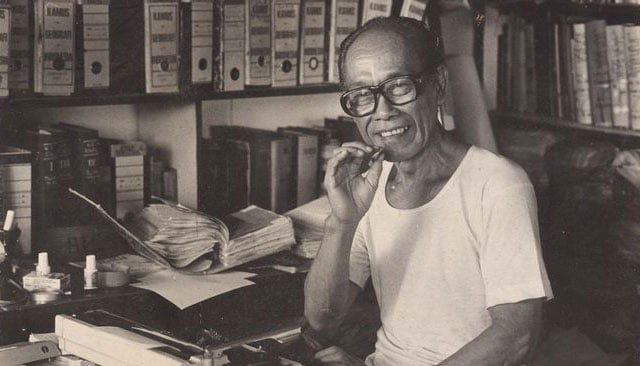

The last time I met Pramoedya Ananta Toer was about 10 years ago in Jakarta. He was not in the best of health and we had very little time to talk. Years of imprisonment had taken their toll on Indonesia’s best-known writer. He was almost totally deaf. But he was, as always, spirited when the word “literature” was mentioned. He joked about millions of students in Malaysia who had read and studied one of his novels—Keluarga Gerilya. It was a compulsory text for Arts students taking the Sijil Tinggi Persekolahan at one time.

And yes, he was pleasantly surprised by the fact that despite Malaysia’s paranoia about communism, the book was used in schools for many years. “Malaysians hated the ideology, but -appreciated a good work of literature when they saw one,” he said. Indonesians hated the writer, the book, and everything about him. His books were banned until recently.

Keluarga Gerilya is the chronicle of a family of nationalists amid Indonesia’s struggle for independence. The heart-wrenching portrayal of freedom fighters resonated with millions of our students. But fame in Malaysia did not bring royalties. And Malaysians are not the only culprits. “My books have been translated into more than 30 languages, but I am the poorest among the famous contemporary novelists,” he joked.

The world sees him as a victim of Indonesia’s suppression of its writers. He was labelled a “prisoner of conscience” by Amnesty International. But many who championed his re-lease and the bid to recognise him internationally did not understand why he was shunned by Indonesian writers after 1965. Mention the name “Pramoedya” in Indonesia and it triggers a debate on freedom of expression and a writer’s moral obligations.

Two years ago, I was asked to speak at an international seminar on Nusantara writers, with special attention to Pramoedya. I had my own dilemma. Should I look at him purely as a writer? Or should I remind my audience of his dark side, when he was the ideologue of the hated Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat (loosely translated as Institute of People’s Culture), better known by its acronym Lekra back in the 1950s?

Lekra became the eyes and ears of the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI), denouncing works that were anti-rakyat or “irrelevant to the struggle”. Freedom of expression was severely curtailed. Writers were labelled, some humiliated, and condemned. Books were banned and open burnings of books became part of “intellectual cleansing”.

Interestingly, Pramoedya was the direct opposite of Senator Joseph McCarthy of the United States in the 1940s and 50s. While McCarthy was looking for communist operatives and sympathisers in Hollywood, Pramoedya’s Lekra was looking for those who were not in line with the PKI-dictated mould of creative work. McCarthy’s “Un-American Activities Committee of the House of Representatives”, set up in 1947, terrorised the film community. Lekra brought fear to artists and writers. McCarthy named names. So did Lekra.

It was his involvement with Lekra that haunted him the rest of his life. When the communist-inspired revolution failed in 1965, members and supporters of PKI were round-ed up; many were tortured and killed, others imprisoned. Under Suharto and his New Order Government, communism became a dirty word.

On the night of Oct 13 that year, Pramoedya was taken by the military. That was the beginning of his life in hell. He was in various prisons in Java before being banished to a penal colony in Buru—one of the first political prisoners sent there. He helped build the prison complex with his bare hands. When he was released on Dec 21, 1977, he was labeled an ex-topol (tahanan politik or political prisoner) that stigmatised him for life.

In Buru, he wrote novels, journals, and notes. Many of his writings never saw the light of day. Some he destroyed for reasons of personal security. The ones that survived, in the form of memoirs and letters to his children, became what is internationally known as Nyanyi Sunyi Seorang Bisu (translated brilliantly by Willem Samuels as “The Mute’s Soliloquy”). It will be remembered as one of the finest memoirs published in recent times.

Many argue that if one Indonesian author deserves the Nobel Prize for Literature, it has to be Pramoedya. But many Indonesian writers would beg to differ. When the Philippines honoured him with the Magsaysay Award for Literature, prominent Indonesian writers wrote an open letter in the Press protesting the decision. The letter, among other things, said: “He led the suppression of the creativity of non-communist writers, dramatists, film-makers, painters, and musicians; he ridiculed freedom of expression, resulting in the banning of books and record labels and initiated the burning of books in Jakarta and Surabaya.”

“I was never a communist, never an organisation man,” he always said. “But I believe works of literature must have a mission.”

In Keluarga Gerilya, the character Sa’aman is asked what makes a good soldier. He says that one needs strength, fortitude, dignity, and, most of all, honesty. Why honesty? If you are honest, you are not afraid to die. “It is only then you will be brave enough to die for the cause you believe in.”

Pramoedya died last Sunday at the age of 81, perhaps believing he would never have to repent for “the cause” while he was in Lekra.

This article was first published in the News Straits Times dated 6 May 2006. Courtesy to Johan Jaaffar for the permission to republished this article in this blog.