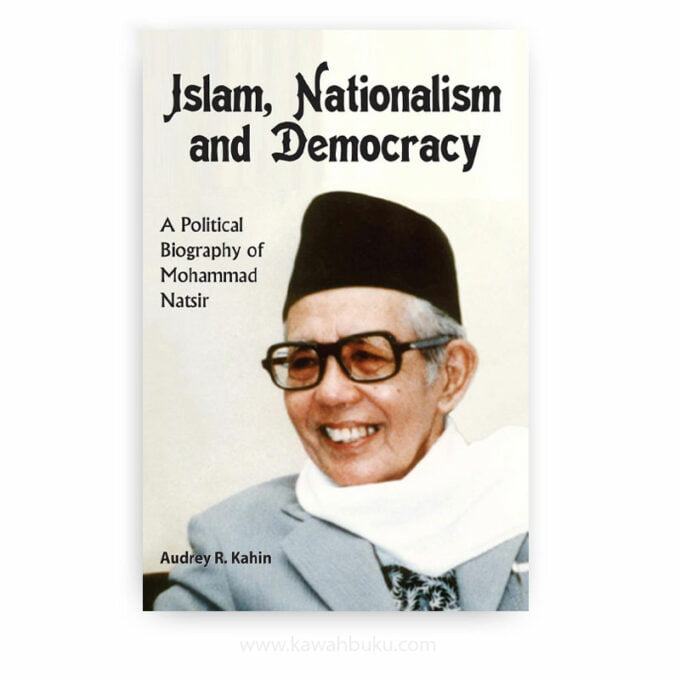

Drawing from a wide range of materials, including these writings and extensive interviews with the subject, Islam, Nationalism and Democracy: A Political Biography of Mohammad Natsir positions an important Muslim politician and thinker in the context of a critical period of Indonesia’s history, and describes his vision of how a newly independent country could embrace religion without sacrificing its democratic values.

Audrey Kahin begins her introduction to this fascinating biography with a description of Mohammad Natsir in late September 1961, crouched on a hillside in the interior of West Sumatra with only a few followers, waiting to be arrested (and very likely killed) by the Indonesian army. Nearly four years earlier he had fled the capital with other senior opposition figures to join rebels in his home province of West Sumatra. But the rebellion failed and with it, Natsir’s hopes of setting Indonesia on a new path, one which would bring about a more decentralized and more democratic form of government, at least compared with the ‘guided democracy’ Sukarno had adopted. Natsir was arrested, but unlike some of his associates, he was not killed.

He was flown to Jakarta and then imprisoned, at first near Bogor; then he was sent by rail with his wife to be kept under house arrest near Malang in East Java. In 1963, as the political situation became tenser, he was separated from his wife and transferred to a military prison in Jakarta. After the coup in September 1965, he and his fellow detainees were kept in detention. In February 1966, they were transferred to house arrest, and after five months were allowed to return home, but they were still confined to Jakarta. Complete freedom was granted only in July 1967.

In 1966, Natsir played a key role in persuading the Malaysian Prime Minister, an old friend, to open talks with Suharto on the normalization of diplomatic relations. But in spite of this assistance, Natsir was never to hold public office under Suharto. He and others from the Partai Sosialis Indonesia (PSI) and Masjumi were distrusted by many in the army and probably by Suharto himself, in spite of their strong anti-communist credentials. Suharto was adamant that leaders from the old Masjumi Party should not be allowed to take leadership positions in the Partai Muslimin Indonesia which was formed in the late 1960s, and allowed to participate in the 1971 election.

Natsir and other old Masjumi leaders were prevented from campaigning, and even before the 1971 elections, Natsir realized that he would not be able to play an active political role as long as Suharto stayed in power. Until his death in February 1993, he occupied himself with forging ties with various Islamic groups in the Middle East. He was one of the signatories of the ‘Petition of 50‘ in 1980, along with many former army and civilian leaders. As a result, he was subject to some petty harassment and banned from travelling abroad, but his immense prestige both in Indonesia and abroad saved him from trial or imprisonment. Only after Suharto’s fall from office did he receive posthumous honours from the Indonesian state, culminating in being made a national hero in 2008.