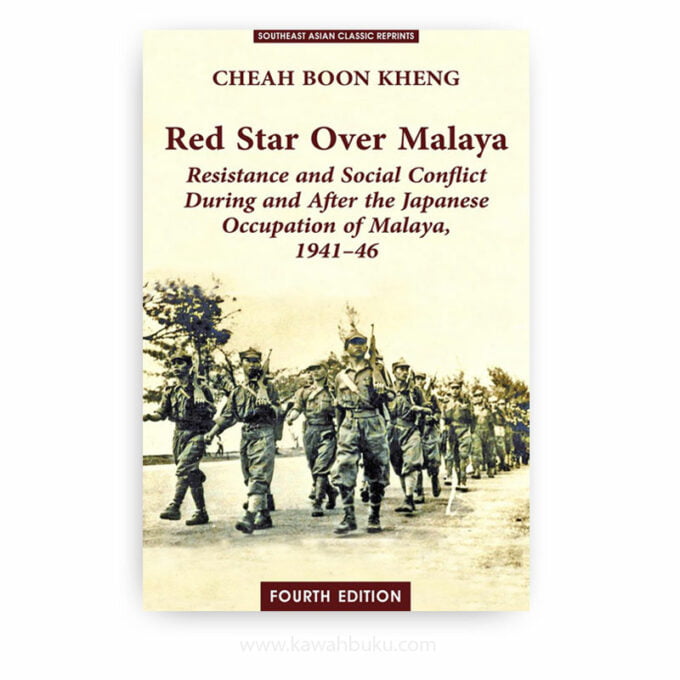

Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation, 1941-46 is an account of the inter-racial relations between Malays and Chinese during the final stages of the Japanese occupation. In 1947, none of the three major race of Malaya—Malays, Chinese, and Indians—regarded themselves as pan-ethnic “Malayans” with common duties and problems. When the occupation forcibly cut them off from China, Chinese residents began to look inwards towards Malaya and stake political claims, leading inevitably to a political contest with the Malays. As the country advanced towards nationhood and self-government, there was tension between traditional loyalties to the Malay rulers and the states, or to ancestral homelands elsewhere, and the need to cultivate an enduring loyalty to Malaya on the part of those who would make their home there in future.

As Japanese forces withdrew from the countryside, the Chinese guerrillas of the communist-led resistance movement, the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), emerged from the jungle and took control of some 70 per cent of the country’s smaller towns and villages, seriously alarming the Malay population. When the British Military Administration sought to regain control of these liberated areas, the ensuing conflict set the tone for future political conflicts and marked a crucial stage in the history of Malaya. Based on extensive archival research, Red Star Over Malaya provides a riveting account of the way the Japanese occupation reshaped colonial Malaya, and of the tension-filled months that followed Japan’s surrender. This book is fundamental to an understanding of social and political developments in Malaysia during the second half of the 20th century.