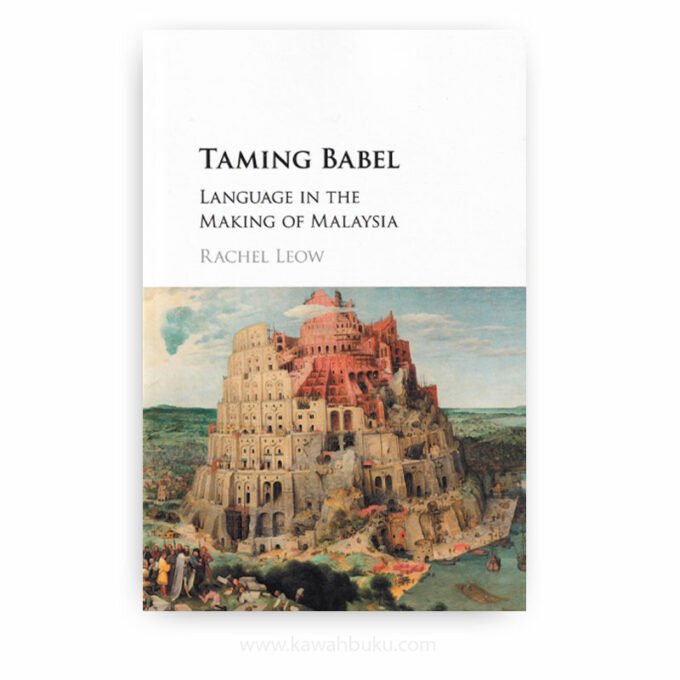

Taming Babel: Language in the Making of Malaysia sheds new light on the role of language in the making of modern postcolonial Asian nations. Focusing on one of the most linguistically diverse territories in the British Empire, Rachel Leow explores the profound anxieties generated by a century of struggles to govern the polyglot subjects of British Malaya and postcolonial Malaysia. The book ranges across a series of key moments in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in which British and Asian actors wrought quiet battles in the realm of language: in textbooks and language classrooms; in dictionaries, grammars and orthographies; in propaganda and psychological warfare; and in the very planning of language itself. Every attempt to tame Chinese and Malay languages resulted in failures of translation, competence, and governance, exposing both the deep fragility of a monoglot state in polyglot milieux, and the essential untameable nature of languages in motion.

She explores the colonial and postcolonial management of linguistic heterogeneity in Malaya/Malaysia across the long century of change from 1877 to 1967 through the early years of British rule, the Emergency period fighting against the Communists, and the years after Independence. In the postcolonial years after independence, Leow tries ‘to make visible an often invisible history of state anxiety over languages’ by meticulously digging into the language technocrats and nationalist politicians’ struggle against the adoption of English as the official language for a new nation; the ‘invention’ and the standardization of the Malay language; the shift from manuscript to print; the cultural transition from orality and aurality to writing; and the orthographic transition from Arabic to Romanized script’.

Using the example of the slogan used by Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, bahasa jiwa bangsa (language is the soul of the nation), she posited that the technocrats glossed over the multiple nuanced meaning of the word bangsa with the result that the word has come to mean race, and not nation, thereby creating the supremacy of the Malay language over others in a plurilingual nation. Similar to the social construction of the notion of ‘race’ in the English language, colonial and postcolonial bureaucrats also constructed the concepts of ‘Cina’ and ‘Melayu’ which became essentialist labels that categorize and subsume a great diversity of peoples and cultures, and come to be imbued with ambiguous meanings related to, and overlapping with, the ideas of language, nation, and state.

In Malaysian politics, the Chinese and Indians’ push for multilingualism and equal citizenship came to be perceived as cultural chauvinism. A postcolonial hegemonic monolingual state order has now created in essence multiple ethnolinguistic nations within one nation-state, with endless contestation over the meanings of ‘race’, nation, and belonging.

Leow suggests this new social reality of the country’s attempt to maintain Malay’s linguistic supremacy, and to manage today’s ethnolinguistic tensions, is also the result of ‘a crisis of hybridity proliferating at anxiously policed borders’. This linguistic hybridity also threatens ‘to create an audience for whom the racially bordered state order is no longer relevant or meaningful’. In the Preface, Leow asks how the ‘language of race (is) kept afloat in a mire of corruption, religious, fanaticism, state repression, and systemic fearmongering’. She wonders if there is hope for a new post-racial political order, and how the ‘book might help to clarify for Malaysians where they have been, where they could yet go, and perhaps, how they might get there’.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet