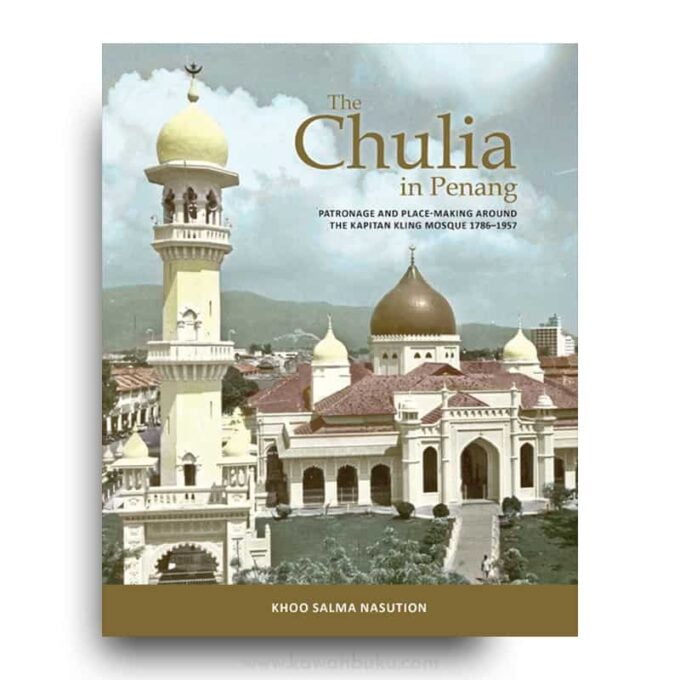

The Chulia in Penang: Patronage and Place-Making around the Kapitan Kling Mosque, 1786–1957 is the first comprehensive analysis of the indigenization of a transnational Muslim diaspora through religious philanthropy and the affinities that exist with the creation of an integrated community, as yet not enveloped or regimented by the colonial state or by its succeeding independent government. This is a paradigm-shifting study for the following reasons.

First it goes beyond the stereotypical narratives of Indian Ocean migration and influences in Southeast Asia. It is also more than a cultural study of transnational families. Khoo Salma, while providing a fascinating perspective on Chulias in Penang and the historical processes that defined their society, politics, and Islam, also illustrates an important microcosm of the city and the state. The dual processes of urbanization, on the one hand, and of religious pedagogy and propaganda, on the other, were achieved through the religious-political symbols of mosques, madrasahs, hospitals and orphanages. Such processes were mediated by powerful philanthropists like Cauder Mohuddeen, a towering presence within the interconnected Asian world. At the same time, these processes were matched by British legal codification of religious charity through the Mohammedan and Hindu Endowments Board to provide protection for their property and special rights and interests. The longue durée pattern of centre-periphery studies of the Indian Ocean often pointed in a different direction, that of a collective Indian impact on Southeast Asia. Here in contrast, by emphasising municipalism, fantasy and imagination in architecture as well as family histories, the study balances the critical transnational commercial and religious affiliations involved in the city port.

The Chulia in Penang: Patronage and Place-Making around the Kapitan Kling Mosque, 1786–1957 introduces a fascinating trail of case studies through that of ‘travelling law’. The British colonial ideal of rule of law, which transmigrated from India to Egypt and elsewhere, is captured here through the narrative of Penang Chulias. Colonial law relating to the regulation of waqf, transferred to Malaya, recognised waqf assets as being held in perpetuity. Specifically, the Acquisition of Land for Public Purposes Ordinance of 1889 was based on the Indian Act of 1863. India’s Mussalman Wakf Validating Act of 1913 also had an impact on the waqf and its operations in Penang. The Indian laws on waqf, creation of trusts, cooperative societies, corporations, schools, and hospitals were all transferred to Penang. This assisted the Chulias to compete with both the Chinese and Western capitalists. By comparison, the Chinese ancestral halls in Hong Kong faced difficulties in seeking similar recognition in terms of perpetuity of ownership of land and fixed assets. The benefit of this legal transplant to the Chulias is highlighted by another comparison with the Hadhramis in Singapore, Who experienced dispossession when facing a powerful independent state and its aggressive policy of appropriating land for development.

Here one can speculate whether, in modern Penang, the Tamil Muslims; emphasis on localism, their preservation of an imagined community conserving power, and their visibility throughout the city landscape allowed them to resist the pressures of homogenization of identity through a strong nation state, such as what was experienced in Singapore. The Tamil Muslims’ intrinsic preservation of a civic rather than national Malaysian identity, intent on protecting their urban iconography through the mosque, entailed powerful political calculations in an ethnically diverse Penang society. This historical localism and extended municipalism, bound by civic consciousness, survives in contemporary Penang, differentiating it from Kuala Lumpur. Penang as a second city preserves its innate autonomy.

In essence, the religious monument of the Kapitan Kling Mosque presented a controlled perception of a liberal city governed by philanthropy while retaining powerful commercial interests. The Foucauldian notion of ‘liberal governmentality’ is implicit throughout Khoo Salma’s study of the Kapitan Kling Mosque since it shapes law, the control of schools and an entire web of civic responsibilities.

Finally, Khoo Salma uses a political interpretation of landmark buildings and urban development to stress the religious origins of Penang’s rise from 1786-1957. In this context too, law is a clever synthesis of local and national with a travelling arsenal of inherited legal codification and practice.

The Chulia in Penang: Patronage and Place-Making around the Kapitan Kling Mosque, 1786–1957, while assessing the role of diasporas and eminent individuals in philanthropy, also experiments with new methodologies of historical significance in the study of cities where strong aspirations for political autonomy persisted. Indeed, Penang’s relations with the national state have always remained fraught, even into the twenty-first century. The urban development of Penang has not lost its Indian Muslim past, which is mustered in defence of its wealthy trading families, even though many of them have relocated to Kuala Lumpur. In Penang, the juxtaposition of a Chinese majority and a Muslim minority has produced not conflict but mutual acknowledgement and pluralism.

The longue durée of India-Malaya relations since 1786 is not a straightforward tale of centre-periphery transmission. Rather, Penang itself was a centre of autonomous political institutions, a free port rooted in trading traditions with an architecture that evoked distinct visual fantasies and a strong religious particularism.

The Chulia in Penang: Patronage and Place-Making around the Kapitan Kling Mosque, 1786–1957 is almost an encyclopaedia on the Chulias, with evocative images that sharply capture their Indianness and Islamic Cosmopolitanism. By occasionally providing an esoteric interpretation to architecture, ceremonial heraldry and costumes — symbols by which the Chulia’s religious and social presence is established — the images may fuel historiographical debates about thé religious history of Islam in the Straits Settlements. It is an excellent book whiCh deserves to be at the top of the league in diasporic studies.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet