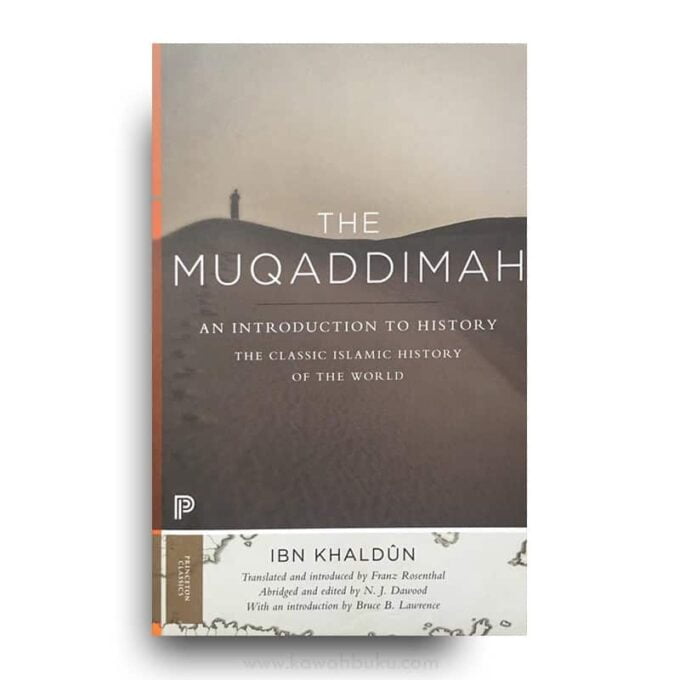

The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, often translated as “Introduction” or “Prolegomenon,” is the most important Islamic history of the premodern world. Written by the great fourteenth-century Arab scholar Ibn Khaldūn (d. 1406), this monumental work established the foundations of several fields of knowledge, including the philosophy of history, sociology, ethnography, and economics. The first complete English translation, by the eminent Islamicist and interpreter of Arabic literature Franz Rosenthal, was published in three volumes in 1958 as part of the Bollingen Series and received immediate acclaim in the United States and abroad. A one-volume abridged version of Rosenthal’s masterful translation first appeared in 1969. Ibn Khaldūn (1332-1406), as is well known, is one of the greatest Arab scholars and thinkers, not because of his monumental history of the Arabs, non-Arabs, and Berbers and their contemporaries up to his own time, but because of the prolegomenon or introduction, The Muqaddimah, which he wrote to this history. The great British historian and philosopher of history, Arnold J. Toynbee (1889-1975), called The Muqaddimah “undoubtedly the greatest work of its kind that has ever been created by any mind in any time or place… the most comprehensive and illuminating analysis of how human affairs work that has been made anywhere.”

Rosenthal’s masterful three-volume translation received wide acclaim in the world of scholarship, as did Dawood’s one-volume abridgment. By adding important sections of Rosenthal’s introduction and a new introduction by Lawrence to his succinct and deftly edited abridgment in this new reprint, Dawood has rendered an important service to students of Islam and medieval history. He could have provided an even more important service had the author included Rosenthal’s bibliography, or even the key sections of it, and enlarged the book’s index to be more comprehensive.

As for Professor Lawrence’s introduction, the only new part of this reprint, it puts Ibn Khaldūn’s The Muqaddimah within more recent scholarship on it, and shows what a continuously engaging work it still continues to be. He edited a useful work entitled Ibn Khaldūn and Islamic Ideology (Brill, 1984) and has written other contributions on the subject; he is thus a most knowledgeable scholar to introduce new readers of the 21st century to Ibn Khaldūn. Lawrence’s way of connecting Ibn Khaldūn’s philosophy of history with the principles of Islamic jurisprudence, which he uses both as a science and a pedagogical tool, is fascinating. He shows, for example, how the principle of ‘ijma (consensus) in the theory of Islamic law functions as ‘asabiyya (group feeling) does in society by mustering a collective will. Furthermore, he cuts through the often bewildering detailed arguments of Ibn Khaldūn in The Muqaddimah to show how his organizational vision considers human civilization moving from manual, physical labor to refined, intellectual pursuits; from desert to sedentary dimensions; from statecraft associated with tribal or religious affiliations to centralized rule, then asymmetric empire; from an almost natural and strong ‘asabiyya that unites society to an effete weakness that invites another civilization to take over.

Dawood’s abridgment of Rosenthal’s translation, now with Lawrence’s introduction, is a good addition to the available works on Islamic history and thought, and makes Ibn Khaldūn’s philosophy of history more easily accessible and understandable.