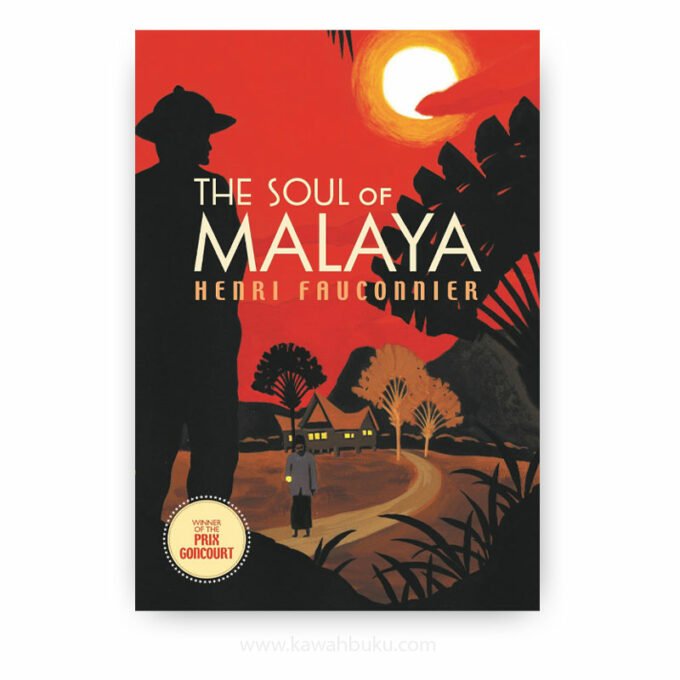

The Soul of Malaya tales the experiences of two French planters, depicts various types of Englishmen running plantations in Malaya, and captures the beauty and appeal of the land. This work is one of those rare novels that is on one level an absorbing drama and on another level, a social commentary. Part memoir, part fiction, the novel continues to capture the imagination with its intriguing character descriptions and “murder mystery” plot, as well as its insights into the Malayan society of the early 1900s.

Without prejudging the quality of modern Malayan literature, one may still class this work as among the few memorable novels in the country. Like Swettenham and Clifford, the author was a European pioneer who resided for many years in Malaya; but his experience as a rubber planter ensures a different vantage point. The title has a pretentious ring, as the plot revolves around the plantation, the key figures are ‘somewhat sophisticated Frenchmen’, and the local flavour is imparted through faithful descriptions of the natural environment and attempts to fathom Malay habits. The other characters provide the foil for the Frenchmen and, with the possible exception of Smail, appear too fleetingly to become life-size. Smail, already a latah, brings on a stock denouement by running amok.

The writing is evocative but hardly Conradian. But the novel’s significance extends beyond the plot. The old Malayan hand may find a familiar paternalism, while nationalists may discover the scheming-because-benevolent exploiter. The historian should gain some insights into the working of a microcosmic plural economy and the mentality of some of its members.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet