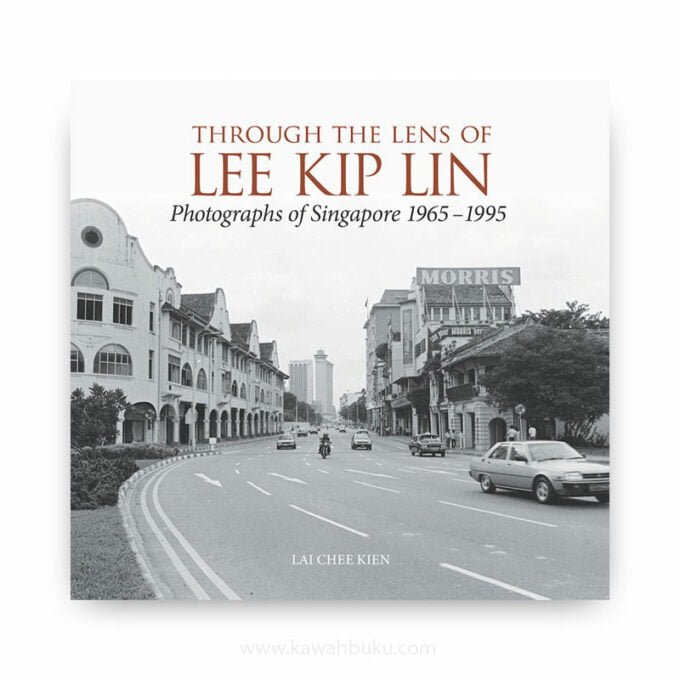

Through the Lens of Lee Kip Lin: Photographs of Singapore 1965-1995 shows about 500 photographs of Singapore by the late Lee Kip Lin that captured the exuberance and eloquence of the different built forms—in an era when time and space in Singapore was more accommodating. Over three decades from 1965 to 1995, Lee systematically photographed land capes, streets and buildings all over Singapore. Lee would take multiple images of each building or street, and each roll of black and white negatives would be accompanied by a contact print sheet for reference. There were also several notebooks in the donated works that contained hand-written information about the location and date of photography.

Lee was concise in his use of photographic negatives; he usually started from larger contexts before moving into smaller ones, from streets to buildings and, where possible, from exterior to interior views. His clear textual descriptions allow us to pinpoint from where the photographs were taken, and permit reference or comparison with other tools such as maps and other types of images. Many of the buildings that he photographed have since been demolished, and several streets have been completely expunged, testifying to the importance and value of Lee’s photographs as documentation material, and his foresight in conducting this arduous exercise.

The author has taken the opportunity to study his photographs, and through careful selection, organised the images under three broad categories in this book: Landscapes and Streetscapes; Houses and Residential Forms; and Other Buildings and Structures. In Chapter One, the images are linked by location rather than a time frame. In the other two chapters, the order of picture arrangement is by architectural archetype.

How do we place Lee’s photographic works among those made by his contemporaries? There are several people who could be summoned in this discussion. Loke Wan Tho (1915-1964), the cinema magnate, was also an avid photographer who had captured many vivid scenes of the Angkor civilisation, besides his pet subject of birds. There were also professional photographers such as Wong Ken Foo (or K.F, Wong, 1916-1998), Kouo Shang Wei (1924-1988) and Yip Cheong Fun (1903-1989). They were award-winning salon photographers who had captured many streetscapes, although this genre was not their main preoccupation. Among the works more closely related to architectural photography were those of Ray Tyers (Singapore Then and Now) and Cheah Seng Kee, whose photographs were included as part of the donation by the Lee family.

Historically and thematically, the closest in relation to the publication format of this book is the 1957 work, Characters of Light, by Marjorie Doggett (1921-2010), which was reprinted in 1985. Doggett’s book showcases her great interest in recording the architecture and street scenes in 1950s Singapore and is organised into seven categories. The book’s original publisher, Donald Moore (1923-2000), was himself a keen photographer.

Why did Lee produce this large collection of images? We can surmise that he felt the need to record his world—a world that would be subsequently erased or changed through swift development. Lee likely had several reasons for photographing these images: as a personal record, as a teaching aid, for illustrations that appeared in his publications, and as a means of documentation. The author recalls a conversation with Lee around the year 2000, when he informed Lee that he would be going for further studies that entailed examination of the nation-building period. His response was a terse “What for? The good architecture was from before that time.”

Reflecting on this statement as the author worked on this book, his remark seemed to echo the author’s own interest in documenting and making sense of the architectural landscape of a cherished past.

From the 1960s onwards, Singapore underwent a tremendous physical change. Developmental plans proposed by the United Nations’ planning consultants translated into urban renewal and housing programmes, which decongested the urban centre and developed housing estates away from it. Lee’s encounter with the third developmental process—land reclamation—was to be a very personal one, and may have triggered his documentation work. During his childhood years, Lee lived with his family at 19 Amber Road in the Katong area, an idyllic seafront property adjacent to the Chinese Swimming Club. He had long enjoyed the area, walking on foot or sailing in his own boat. In 1969, however, reclamation along the east coast of Singapore was carried out; the process swiftly erased the swimming structure next to his home and pushed out the coastline, extending the land outwards for a further kilometre or so for future constructions. Lee took a large number of colour slides to record the reclamation. In the late 1970s when the house became ‘intolerable to live in’, he moved out.

Three special features are included in this book to demonstrate how we may further make sense of Lee’s photographic collection, as well as use it as a resource for future research. The first special feature serves to visually document the Amber Road reclamation from 1969 to 1970. The second and the third features attempt to reconstruct, respectively, a now-demolished village (Chong Pang in the northern parts of Singapore) and an expunged house (Panglima Prang near River Valley Road). For the latter two sections, building plans, maps and photographs, considered in relation to each other, assist us in visualising spaces and places no longer in existence in Singapore.

New possibilities of research and reconstruction may open up if we contextualize the photographs from this book with other published or virtual collections, as well as other textual media. The photographs in the Lee Kip Lin Collection, held by the National Library, represent an important document of architectural and urban history in Singapore, filling the gap between the works of early architectural photographers such as Marjorie Doggett in the 1950s, and those of the subsequent generation, such as Albert Lim and Darren Soh from the 1980s onwards.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet