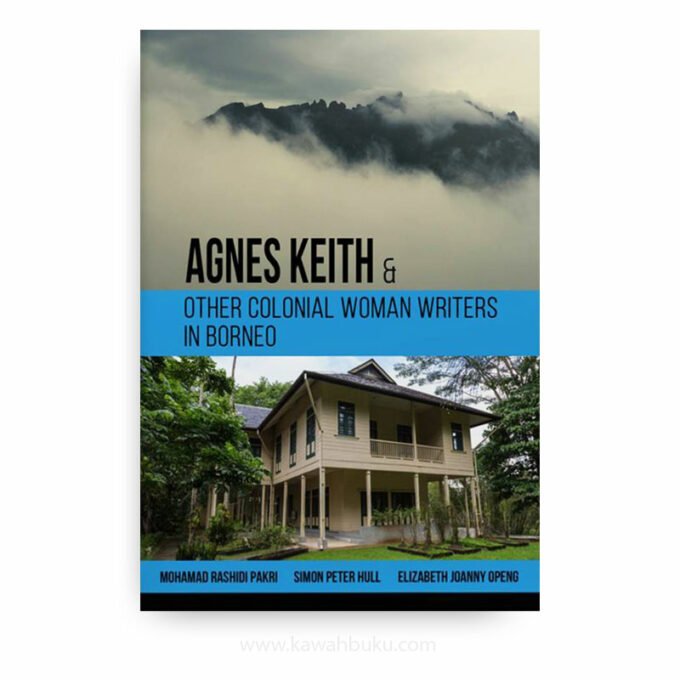

Agnes Keith and Other Colonial Women Writers in Borneo testifies to the great diversity of such writing and uniquely does this by showing the existence of a richly varied and heterogeneous range of text not only between man writers and woman writers but, equally, amongst the women themselves. These are women, moreover, who are writing within the same relatively small region of South East Asia. As Agnes Keith, whose writing forms the focal point of this book, credibly surmises, Borneo remained, even towards the end of the colonial period, a dark and mysterious land to people in the West, largely populated, as they imagined, by tribes of headhunters.

At its core, this book questions the very concept of “colonial” writing and, by extension, any such conveniently generalising terms and the assumptions which they inevitably attract. Similar to the problematic relationship between the historical notion of a “Romantic” period (which itself remains open to dispute) and the aesthetically and politically diverse writings of “Romantic-ism”, the colonial period accommodates a broad range of writings from implicit imperialist apologetics to riotous satire at the expense of the empire. A contradiction thus emerges, as acceptance of a historically designated colonial period seems to presuppose, in turn, a homogeneous corpus of literature, a unified cultural manifestation of “colonial-ism”.

Douglas Kerr implicitly acknowledges the unwieldy diversity of colonial literature in the introduction to his study of the simultaneously assertive and anxious texts of British colonial writers in the East, when he summarises the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as “a period when the British empire reached its fullest extent, and when writing about the East was extremely rich, varied and contentious”. Where the geographical scope of the present study is concerned, or at least in the land adjacent to it, the range of colonial literature can be marked on the one hand by Frank Swettenham’s authoritative dissection of the Malay people, in The Real Malay (1899), and on the other by Anthony Burgess’s caustic rendering of Britain’s final withdrawal from South East Asia, in a series of comic novels originally published between 1956 and 1959, and later collected in The Malayan Trilogy (1972).

Kerr, moreover, confesses his study to be highly selective, “a tiny fragment of the available literature,” and his book notably focuses on male rather than female writers. The arrival of postcolonial feminism in 1980: has seen studies that have challenged criticism’s tacit reification of the patriarchal bias of colonialism itself, by exclusively studying women writing: three such studies are by Kirsten Holst Peterson and Anna Rutherford (1986), Anne McClintock (1995), and Oleh Jyotsna Singh (1996). These and other studies have generally argued that colonial women writers tended to be more ambivalent than the men about the masculine world of empire-building and administration, due to a marginalised status within their own society: “Women travellers, it was pointed out, necessarily stood in an ambiguous relation to the colonial or expansionist projects pursued by their nations, being simultaneously ‘colonized by gender, but colonizers by race'”. This manifests itself in a greater focus on the domestic realm to which the colonial wife was confined much of the time, leading to a more sympathetic identification with, and less clinical detachment from, the native people, especially the women.

Yet the danger of opposing women’s to men’s colonial writing is that we end up with two simplistically homogenise groups, defined merely by mutual difference, a consequence only marginally preferable to the singular concept of colonialism with which we started. It has, therefore, been our intention to avoid writing a postcolonial feminist study that paradoxically stereotypes women (as well as men) writers. We will see, for example, how much more intimate and interactive was Margaret Brooke, the wife of the second White Rajah in North Borneo, with the native people, in comparison with her more aloof and sceptical daughter-in-law, Sylvia Brooke. It occurred to the present authors that the same sense of lively heterogeneity can be found in the conflicting accounts of travels in the Malay states in the 1870s, by Isabella Bird and Emily Innes, the latter actually writing, and entitling, her book, The Chersonese with the Gilding Off (1885) as a gritty response to the more sanitised content of Bird’s, The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither (1883).

In summary, then, the present book emphatically testifies to the great diversity of colonial writing, but it does so by showing the existence of a “rich, varied and contentious” range of texts not only between men and women writers, but equally amongst the women themselves. These are women, moreover, who are writing within the same relatively small region of South East Asia. As Agnes Keith credibly surmises, Borneo remained, even by the 1930s, a dark and mysterious land to people in the West, largely populated, as they imagined, by tribes of head hunters. Hence it was a land, perhaps, not as well known as the other, more publicised Asian territories in India, Malaya and Singapore. It was, therefore, to the lack of knowledge and curiosity of ordinary middle-class people in the West that Keith’s writing, and that of the other women writers featured in this study, so engagingly responds.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet