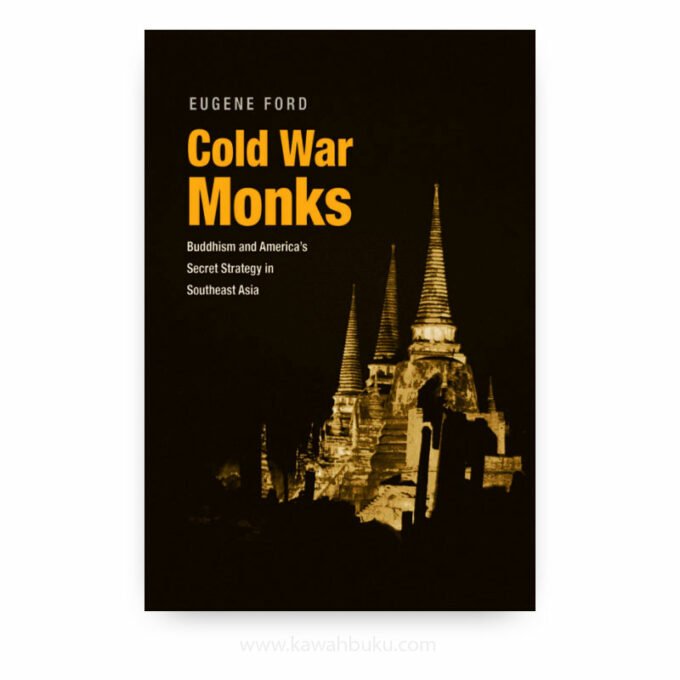

Cold War Monks: Buddhism and America’s Secret Strategy in Southeast Asia provides a groundbreaking account of U.S. clandestine efforts to use Southeast Asian Buddhism to advance Washington’s anti-communist goals during the Cold War. To answer the question of how the U.S. government made use of a “Buddhist policy” in Southeast Asia during the Cold War despite the American principle that the state should not meddle with religion, Eugene Ford delved deep into an unprecedented range of U.S. and Thai sources and conducted numerous oral history interviews with key informants. Ford uncovers a riveting story filled with U.S. national security officials, diplomats, and scholars seeking to understand and build relationships within the Buddhist monasteries of Southeast Asia. This fascinating narrative provides a new look at how the Buddhist leaderships of Thailand and its neighbours became enmeshed in Cold War politics and in the U.S. government’s clandestine efforts to use a predominant religion of Southeast Asia as an instrument of national stability to counter the communist revolution.

The United States had many weapons to use against the Soviet Union—from missiles to development aid to blue jeans and cans of Coca Cola. Among the most important were what President Dwight D. Eisenhower called “spiritual weapons,” by which he meant the mobilization of religious communities against communism. Ford’s focus is primarily on Thailand, with substantial sections as well on Vietnam and Cambodia. He argues that the Cold War forced Thai Buddhism away from “its closed, indeed closeted, approach to the world outside Thailand” to become “more diverse, more political, and more internationalized under Cold War pressures”. Ford is also attentive to the evolving U.S. foreign policy toward Buddhism in Southeast Asia from the 1940s to the 1970s.

This policy developed haphazardly. In 1951, long after Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman had cultivated ties with Christian organizations, American officials in northern Thailand began encouraging Buddhist monks to speak out against communism in this rural region. Only in 1957, after the French lost control of their Vietnamese colony, did the United States create a systematic approach to Buddhism. Weary of meddling directly in religious affairs, the foreign policy bureaucracy funnelled money through the San Francisco–based Asia Foundation, one of the many Central Intelligence Agency front groups in the Cold War. The Asia Foundation helped fund the World Fellowship of Buddhists, encouraged inter-Buddhist dialogue, brought monks for visits to the United States, and facilitated exchanges between Southeast Asian monks and American academics, all in the hopes of stimulating anticommunism among Buddhists abroad.

The benefits from the millions of dollars spent appear to be meager, and by the early 1960s the Asia Foundation cut back its programs. Seemingly, the most important part of America’s Buddhist policy is what it missed. As Vietnamese monks began protesting against the repressive Catholic government in South Vietnam, Buddhists in neighbouring countries noticed and began expressing concern by 1961. American officials “missed the writing on the wall,” Ford observes and were blindsided two years later when a Vietnamese monk set himself on fire. The final chapters of Ford’s book show that American meddling had its most important effects on Thailand’s religious orders, which emerged from their Cold War experience more politically active and internationally-minded. Thorough research in Thai archives, the Asia Foundation papers, and American foreign policy archives makes Cold War Monks a welcome contribution to our understanding of the role of religion in the Cold War and U.S. foreign policy in Southeast Asia

Reviews

There are no reviews yet