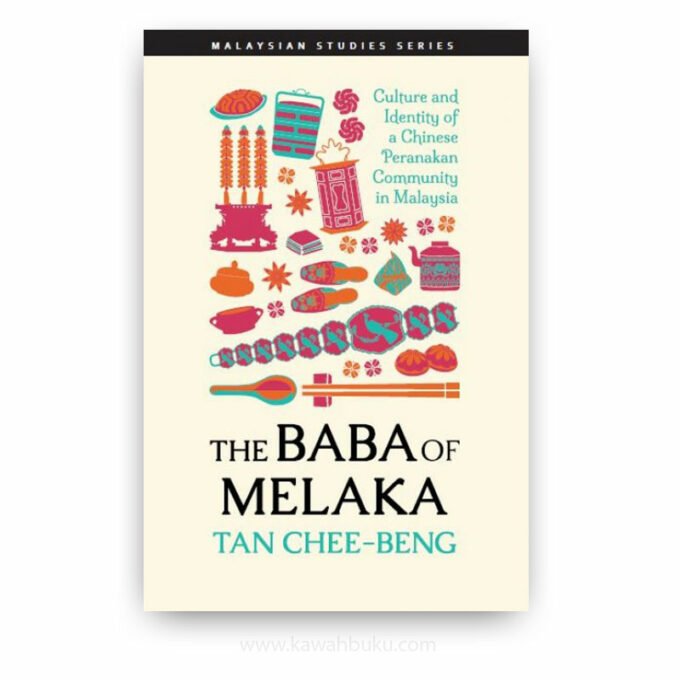

The Baba of Melaka: Culture and Identity of a Chinese Peranakan Community in Malaysia is an ethnographic study that provides a comprehensive description of Baba culture and identity in Melaka, by analyses the term Baba, the development of Baba society, their distribution in Melaka and overt features of identity, the Baba Malay dialect, customs and religion, kinship and social interactions—all of which tie into changes in Baba identity.

Tan Chee Beng’s study of the Baba (also Peranakan or Straits) Chinese of Melaka is based on extensive fieldwork conducted in the late nineteen-seventies for a Ph.D. at Cornell. It discusses and illustrates with many photographs a number of facets of Baba culture and society, though the main emphasis is on ethnicity and ethnic change.

Once a powerful and prestigious sector of Malayan colonial society, the Babas are ridiculed by other Chinese for what once made them great—their extensive acquisition of Malay language and culture in place of their own. The transformation is apt to strike the outsider as a sad tale. To those who know Malaysia and its deep ethnic divisions, the Babas would seem to have exemplified a bargain that should have been struck more generally and permanently between Malays and Chinese. It is a bargain that was struck only in a few places and times and then only partially. In recent years it has been rejected by the masses of both the Chinese and the Malays.

Melaka, the area studied by the author, is the area formerly occupied by the Malacca Kingdom. Later, as part of the Straits Settlement under British colonization, it was one of the areas in which there was an early settlement by Chinese immigrants. The children and descendants of the offspring of Chinese immigrants and local Malay women are called “Peranakan” in Malay. “Baba” refers to the Chinese descendants among the Peranakan who have not maintained the use of the Chinese language.

Baba speaks Baba Malay, and many are also fluent in English. Although their knowledge of the Chinese language is very limited (many are descended from immigrants from the province of Fujian), they are proud of their “Chinese heritage.” Thus “Baba” is a label that refers more to a group defined by cultural rather than racial characteristics; it refers to a sub-ethnic group that should be classified by ethnicity based on language, daily customs, and consciousness of ethnic identity.

As for the structure of this volume, after the introductory chapters, the author gives an overview of Baba history and demography, outlining the basic structure of the Baba community and the process whereby it was formed. Chapters 3 through 8 concern the main theme of this study, i.e. what are the Baba? The author presents the Baba’s ethnic identity, their language, their customs and religion, kinship,and ethnic change.

Chapter 5 focuses on the fact that the Baba share Chinese folk religion with non-Baba Chinese, and that the Baba ethnic identity is both Baba and Chinese. Chapter 6 on death rituals shows that Islam and the Chinese religion are conspicuous symbols that indicate ethnic boundary and ethnic identity. Baba is more active than non-Baba Chinese in maintaining traditional rituals that have filial piety as their core. Also,although traditional rituals have been influenced somewhat by Malay culture, the world view and ethos remain practically unchanged. Chinese customs and Chinese religious ideology are steadily maintained, almost as a substitute for the loss of Chinese language, and act to strengthen Chinese identity.

This study is not only a comprehensive ethnography of the Baba, but also contributes to the discussion of the relationship between acculturation and ethnic identity. The author is himself a Chinese Malaysian; he contributes theoretically to this theme by discussing it from his individual point of view.