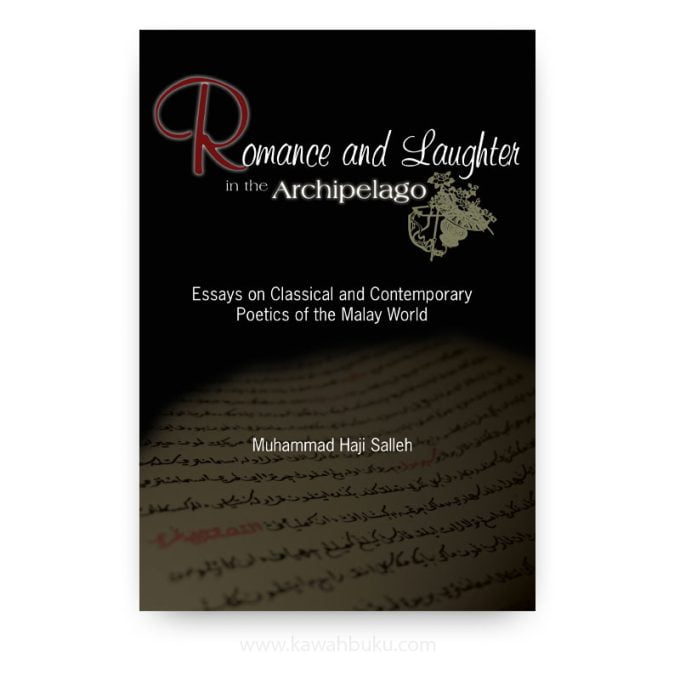

Romance and Laughter in the Archipelago: Essays on Classical and Contemporary Poetics of the Malay World retrieve traditional concepts of Malay literature embedded in the texts of the Malay Archipelago including Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei and Indonesia. It defines the perimeters of literary art, its function, author and texts, and subsequently seek out elements of literary beauty as defined by numerous writers and oral storytellers. However, with modern Malay literature’s new predicament and confrontation with the West, a clash of cultures is strongly discernible in the lines and tones of these works.

These essays are among Muhammad Haji Salleh’s most seminal works, offering new insight into the rich earth of an extraordinary fecund and sophisticated literature. This selection of essays is the product of the many journeys taken after the first series of forays, i.e. after the publication of Yang Empunya Ceritera: The Mind of the Malay Author (1991). It is now 24 years after. The author has gone deeper into certain concepts and has even written a theoretical description of Malay literature, Puitika Sastera Melayu (2000). These essays are interlocked into the theory, into the concepts the author tried to sketch in that book.

Many of the papers began life as keynote addresses, in Malay or in English, as conference papers, and some also as notes on readings and attempts at collecting terminologies.

As they cover an extensive field of study the author has tried to divide them into five fields of concern. The first deals with the great magical Malay pantun, and also its related form, the mantera, incantation. Muhammad Haji Salleh have tried to trace its history and spread across the islands and also to other parts of Southeast Asia, showing that it is a form favoured by at least 35 regional languages. He was intrigued by the ‘magic’ of this quatrain, its intricate aesthetics of compactness and minimal poetics. Furthermore, it is a form based on the sounds and structure of the melodious Malay language, and a philosophy of the people in which nature is seen as a complement of the human world. It has attracted so many people and so many races that they gave popular functions in their society, and in some communities, for over at least a thousand years.

Perhaps, in the last analysis, it is its basic and simple qualities, a stable and natural rhyme-scheme, the structure in two interlocking and complementary part, that encourages all groups of people, from the farmer to the Prime Minister, from the shaman to the young housewife, to partake in its composition. It has undoubtedly become the people’s form, offering both the simple and the sophisticated.

The manteras (incantations) are as intriguing. Used for enhancing everything from sales of goods to a bright and lovely complexion and defence against wild animals or wilder human beings with a design on a victim, it is perhaps one of the oldest forms of free verse. On the other hand, it is famous for its curative purposes. Love manteras, on the other hand, use the medium of mellifluous words to woo and enhance the complexion and confidence of lovers.

The second part of Romance and Laughter in the Archipelago attempts to harvest native concepts and theories from the many texts across the Archipelago, as a basis for the understanding of local literature. Thus, the author has tried to refer to as many texts as possible, in both the manuscript or book form, from as many libraries in Malaysia or overseas as possible. Central native terms such as karang, pujangga, dalang and ikat-ikatan, karangan berangkap or karangan berirama have their own special concepts, usually quite different in their fields of meanings from the Western ones. It is from these terms that the author moved on to look at the different concepts central to a theory of literature the meaning and the qualities of sastera, sejarah, pantun seloka, pengarang, pujangga, dalang, endah dan indah, bahasa yang indah-indah, khalayak, manfaat, and khidmat.

The third part in Romance and Laughter in the Archipelago: Essays on Classical and Contemporary Poetics of the Malay World brings us into the wonderful yet quite mysterious world of orality. As Malaysian literature is shot with oral qualities, even in the modern works of Usman Awang and Shahnon Ahmad, the influence of its culture on authors, the structure and sound of their works are indeed a passionate area of debate. The original legends and myths belong to the first orality, but these aforementioned writers and many of their contemporaries may be classed into what is known as secondary orality, one that has been interrupted by new technology and mass media, but which sometimes also acts as a defence against contemporary written styles; in the final analysis they may be read as a statement of identity. The author has also crossed over the straits to Indonesia to look at the powerful oral poets of the 19803 and 1990s, namely Sutardji Calzoum Bachri and Putu Bawa Samar Gantang. The former is a sophisticated and conscious interpreter of the Indonesian language, even equipped with his own manifesto on the nature and meaning of words. The latter’s orality, however, is radically different, for it is buried in rituals and ritualistic trance.

The fourth part of these essays foregrounds literature as a medium of instruction or entertainment, which determines not only the type of work created but also the aesthetics of literature itself. Its didactic nature is traced to the early oral stories, through the chirographical Sulalat al-Salatin and Hikayat Isma Yatim, and most of the works of the modern poet, Usman Awang. What seems to be clear is that the concept of ‘good’ literature has been value-added with melodious language and sweet-sounding poetry. Literature, more often than not, is composed of instruction, for the dissemination of common social values and showing the listener and reader the exemplary heroes, their personalities and deeds that should be emulated. However, when the religious content is more dominant, then religious instruction is given a broader space, and meaning; when the social slant is heavier, then the social values take precedence.

These essays in Romance and Laughter in the Archipelago are a product of a long and continuous attempt to understand Malay concepts of literature, to appraise great works and to consider paths to further research. The author has been encouraged by many scholars who could see the new paths that he has taken and has helped to refine his manuscripts. Unfortunately, there are many others who are buried in their colonial or conservative caskets, who feel threatened by any return to one’s traditions and roots.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet