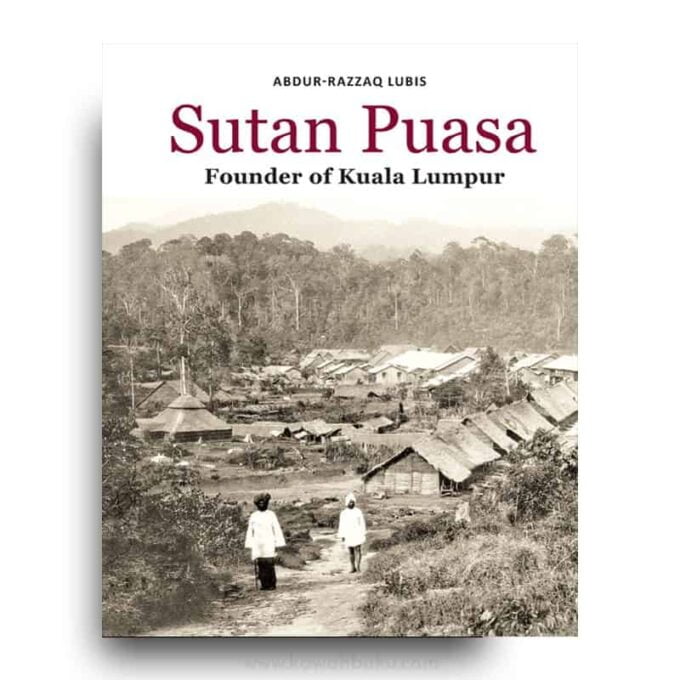

Sutan Puasa: Founder of Kuala Lumpur focuses on the life of Sutan Puasa, a Mandailing migrant to Selangor who played a central role in the early period of tin mining in Kuala Lumpur that occurred in the mid-nineteenth century. It suggests that Sutan Puasa was a key figure in the establishment of a mining and trading settlement in the historically accepted site of Kuala Lumpur, years before conventional historical narratives had dated the foundation of Kuala Lumpur by the Kapitan China, Yap Ah Loy. Lubis’s decision to focus the narrative of the book on the role of Sutan Puasa is motivated in part by the fact that, while he is ‘a son of Kuala Lumpur’, he is descended from a relative of Sutan Puasa and has strong cultural and familial connections with the Mandailing community in Malaysia. This brings us to the significant aspect of this work. The book is indeed a fine example of the way an intensely felt and carefully researched local history can provide information which forms the basis of the kind of ‘re-interpretive history’ that all nations need.

Sutan Puasa: Founder of Kuala Lumpur presents an alternative historical narrative (based on a careful review of historical evidence), different from the prevailing versions which have fed into the nationalist narratives that had been emerging since independence in 1957. More specifically, Lubis provides convincing answers to two deceptively simple questions: first, who was the true founder of Kuala Lumpur? and second, are the existing historical accounts of the founding of Kuala Lumpur accurate?

Sutan Puasa: Founder of Kuala Lumpur feeds into the debates about the ‘in-between’ periods of Southeast Asian history before colonial rule created fixed national boundaries. Thus, there is ample evidence that the pre-colonial period in Southeast Asia was characterised by migrant networks that utilised the ambit of boundaries as well as territories that existed as ‘in-between spaces’ of the geographical region of Indonesia and the Malayan Peninsula. These networks involved the movement of Bugis, Boyanese, Javanese from eastern Indonesia and the Sumatrans, including migrants from Minangkabau, Mandailing, Rawa and Kerinci.

They settled primarily in the western parts of the Malayan Peninsula and the colonial outposts of Malacca (Melaka), George Town and later Singapore, seeking out ecological niches for agriculture and occupations familiar to them from the experience of their homelands. The networks were of two kinds:

The first type of network consisted of migrant agricultural colonists who were seeking new land in the empty frontiers of the western Malayan Peninsula. They tended to come in small groups, each group led by a headman, setting up a form of chain migration that subsequently brought Village members to the Malayan Peninsula. An example of such migration involved the movement of migrants from the Minangkabau homelands in Sumatra to Malacca and Negeri Sembilan These movements were sometimes associated with events in their home region. In the case of the Mandailing, the Padri Wars (1803-1845) had created disruptive conditions in their homeland.

Intertwined with this was the occupational networks through which Indonesian migrants had been moving to the urban centres in west coast Malaysia. The Mandailing movement to Kuala Lumpur and its environs was motivated initially by their desire to engage in tin mining, according to techniques 0f extracting tin developed in their homeland. They were also involved as traders. As the community increased in size, there was agricultural colonisation, particularly in the areas upriver of Kuala Lumpur, and also Ulu Langat.

Another reason why Sutan Puasa: Founder of Kuala Lumpur compelling is that it is situated in 3 wider geographical context of trans-Indonesian Malay hybridity and interaction Lubis understands the hybridity of these ‘in-between’ historical eras, the multiplicity of actors, the diversity of cultural understandings and practices: that are necessary for the writing of Malaysia’s history. He also shows how this extraordinary, complex milieu provided the fluctuating framework for the accommodation, coalition building and resistance that developed between the Malay Sultans, their rajahs, the Mandailing migrants, and the Chinese miners as the British began to establish their political control before Kuala Lumpur waS designated as the administrative capital of the Federated Malay States in 1896.

Sutan Puasa: Founder of Kuala Lumpur also echoes concerns in earlier study on the matter, that had been articulated in a far less convincing manner. First, Lubis recognises that the idea of the ‘Malay’ in the nineteenth century included not only riverine-based sultanate of the west coast, but also the migrant communities from Indonesia that were moving into the Malayan Peninsula. The relationships between Malays and Indonesians exhibited great diversity in different locations that reflected cultural, economic and social differences, which were characterised by much fluidity. His historical account of process seen through this exhaustive account of the life of Sutan Puasa and the Mandailing community illuminates this diversity in time and space as they struggled to become a legitimate component of the growing population of Kuala Lumpur and Selangor. Furthermore, his study provides more fuel to attack the colonial stereotypes of the Malay as being geographically immobile and resistant to urban life.

Of course, there is nothing new in such attacks of these colonial stereotypes. They were part of the intellectual excitement generated by Ungku Aziz and Syed Hussein Alatas in Malaysia in the 1960s and 70s, echoed in Tun Mahathir bin Mohamad’s book The Malay Dilemma (1970), that led to the development policies which have fuelled the urbanisation process and the remarkable movement of rural Malays to the urban areas of peninsular Malaysia. Today, as part of the broader category of Bumiputra, they make up a majority of the urban population of West Malaysia for the first time since the beginning of the nineteenth century.